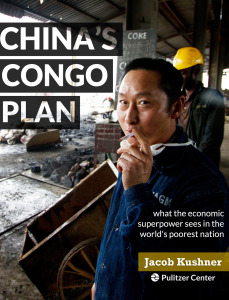

Emmanuel Tshiteta crouches over a pile of copper ore he recovered near a mine in Kolwezi. / Jacob Kushner

Journalists often consult a range of sources as possible to get an accurate picture of their subject. But sometimes there’s a single source who seems to know almost everything—an expert who’s the ‘gatekeeper’ to a castle of information and contacts on the business or deal the reporter is investigating. Enlisting the help of this person can unlock access to dozens of key sources and documents all at once.

This happened to be the case when I was reporting my master’s thesis for Columbia Journalism School about China’s rise in the Democratic Republic of Congo, now an eBook. I was investigating a $6.5 billion “infrastructure for minerals” deal in which the Chinese state-owned companies partnered with Congo’s state mining agency to mine an incredible 6.8 million tons of copper and 427,000 tons of cobalt over the subsequent 25 years. In exchange for the minerals, the Chinese companies would spend $3 billion to build roads, hospitals and universities throughout Congo. That investment was not structured as a gift, but a loan: every dollar spent will eventually be paid back in copper revenues.

Johanna Jansson

The more I reported, the more the name Johanna Jansson came up: It seemed like every journalist, academic and business insider I spoke with about the deal would refer me back to her. Jansson is a Swedish PhD candidate who has spent years researching the specific megadeal I was reporting on, called Sicomines, for her dissertation at a University in Denmark. In January 2013, I approached her in Kinshasa to ask for help understanding the deal—and for her contacts to some of the most powerful and knowledgeable stakeholders in Congo. My eBook, supported by the Pulitzer Center, would not have been possible without the information and contacts she provided me.

But what motivated her—an academic expert and a business insider—to open up to me—a journalism school student and someone with relatively little knowledge of the subject? What inspired her to hand off to me information that she had spent years gathering?

Nearly two years later I called her to discuss what a journalist can do to gain the trust and help of an expert– and what that expert often expects from the journalist in return.

Jacob Kushner: By the time we met you’d already spent years of your life studying this deal. It was your ‘baby’ so to speak, and you had years to go before your dissertation would be completed and published. Why would anyone in that position be willing to share?

A Chinese employee of a major, Chinese state-owned construction company watches over a Congolese employee in Kinshasa. / Jacob Kushner

Johanna Jansson: I was a bit scared in the beginning, to say ‘oh no, someone will be toe-treading me.’ But I’ll take the risk of sharing because I know I get stuff back from people. If you trust people then you really get stuff back. I deal with journalists in the field and those people that I talk to are real professionals, they know what the rules are. If you steal information you’re dead—professionally dead and reputationally dead.

Kushner: But what do you mean by steal? The very goal of the journalist is to publish everything he or she can learn, right?

Jansson: I mean without credit. In academia people go over the top to say this came from that person and this person did that…If you want to use my currency, which is thinking, then I would appreciate to be acknowledged by that. It’s good for me for my reputation to be mentioned as an expert.

But engaging with media or the public gets you nowhere in your career. The only thing that promotes you is your academic work and your teaching. So any engagement with journalists is on your spare time…that’s why so many academics don’t do it. They have kids, they need to publish.

Kushner: When I first came to you I must have sounded like I didn’t know what I was talking about. What gave you confidence that, at the least, I was really committed to figuring it out?

A man rids his bike across the vast mining lands outside Kolwezi in southeastern Congo. / Jacob Kushner

Jansson: I probably thought, ‘wow this is a big topic to try to bridge in such a short time.’ But I was impressed afterwards because you really did do it. (At first) you were asking really basic questions for someone who was trying to grasp something so big. (But then) you ran around like somebody on speed, talking to everyone in a second, and then you produced something that was really good.

Kushner: Many journalists are hesitant to let a source review what they intend to write or publish. But would you have spoken to me so freely if I hadn’t offered to do that from the start?

Jansson: I wouldn’t talk to a person that doesn’t do that. Because most conversations flow off and on the record, and it would not be possible.

Kushner: What about sharing your contacts—were you nervous about sharing them with me, especially one particular high-up government official?

Jansson: I didn’t connect you—that was Lizzie (Parsons) from Global Witness who did that. But I would have. It’s about economy—if I help you then you’ll help me. The official you mention was stonewalling me, but he wanted to see you. You got some things out of him that I didn’t know. It’s an economy, a barter network. (Note: Immediately after interviewing the government official, I shared it with Johanna. Although she might see this as part of our journalist-expert ‘barter,’ she also did a service to me by double-checking that I was interpreting the interview accurately).

Kushner: What obligation do journalists have in a scenario like this—one in which they’re depending on an expert like you?

Jansson: I think journalists have an obligation not to simplify things so much as to get it wrong. I think they can meet halfway. The New York Times published a story about oil in African countries, the Chad case–you and I talked about this. The journalist portrayed it as if the Chinese were the only companies making problems in the oil sector.

Kushner: OK, but how did you know from the start that I wasn’t going to oversimplify China’s engagement in Congo as well?

Jansson: You were talking about how you learn to doubt yourself—I think journalists could really do that more. A lot is about what words you use. If you say the Chinese are doing it, or it seems like they are doing this…there’s a huge difference even in the conjugations of the verbs you use. Are you getting to sensationalism, or are you using a proper analysis?

Kushner: What’s the most important thing any business reporter should do when approaching an ‘expert’ to ask his or her help?

Jansson: Read their stuff first. Because it’s tiring when people come and say, ‘can you tell me this’…and ‘this’ is (already) in a publication. See if any of their publications are available and if they are, take the time to read. Then approach them and say ‘I read this and that,’ or ‘I’ve looked at your publications but I haven’t had time to read, but can you explain to me this and this?’ In academia you’d never ever approach professor and ask, ‘what’s your research about?’ In academia you do your homework, or you keep your mouth shut.

Kushner: Is there anything that academic ‘experts’ like yourself can learn from journalists?

Kushner: Is there anything that academic ‘experts’ like yourself can learn from journalists?

Jansson: I think our jobs are not as different as people tend to think. I think that all academics should be able to convey what they’re doing. You know, the elevator pitch? All academics should have an elevator pitch.

One journalist friend of mine will comment on my stuff and say, ‘this is way too much jargon! Why don’t you just say what you want to say?!’

***

Jacob Kushner is a freelance journalist reporting on foreign aid, immigration, international human rights law, extractives in developing nations, and foreign investment in Africa. His eBook, China’s Congo Plan, was favorably reviewed in The New York Review of Books.

You can read Jansson’s first study, The Sicomines Agreement: Change and Continuity in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s International Relations, here. You can read Jansson’s second study, The Sicomines agreement revisited: prudent Chinese banks and risk-taking Chinese companies, here.

This interview was originally published in 2014 by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism’s ‘Covering Business’ blog.