In Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the lakes are flooding farmland, swallowing communities and leading to deforestation, baffling climate scientists.

Jacob Kushner

Story and photos by Jacob Kushner for National Geographic

In Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the lakes are flooding farmland, swallowing communities and leading to deforestation, baffling climate scientists.

Jacob Kushner

Story and photos by Jacob Kushner for National Geographic

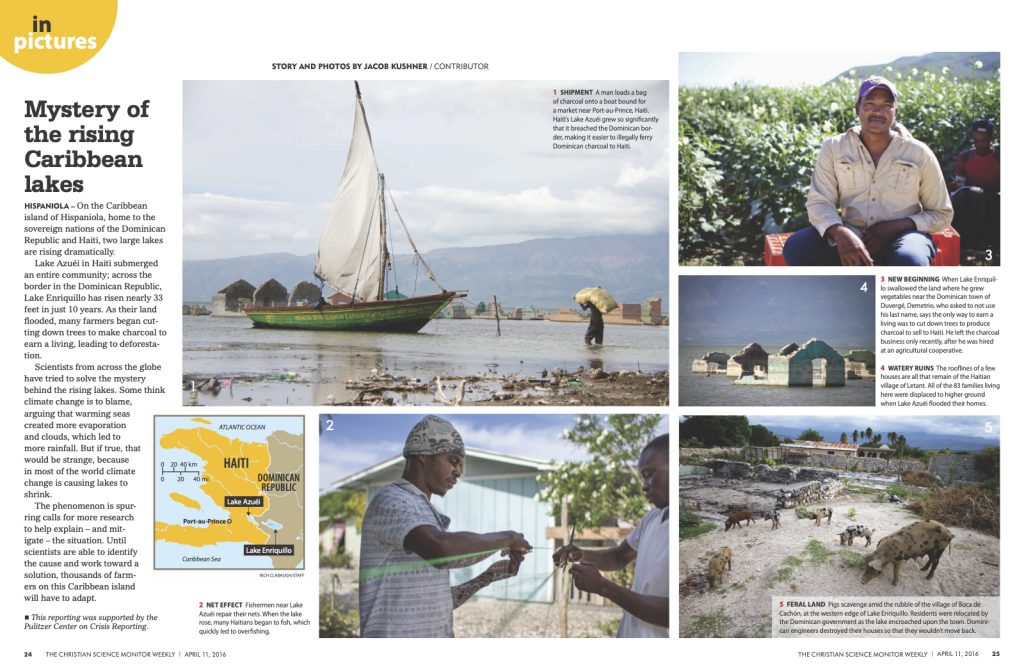

HISPANIOLA – On the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, home to the sovereign nations of the Dominican Republic and Haiti, two large lakes are rising dramatically.

Lake Azuéi in Haiti submerged an entire community; across the border in the Dominican Republic, Lake Enriquillo has risen nearly 33 feet in just 10 years. As their land flooded, many farmers began cut-ting down trees to make charcoal to earn a living, leading to deforestation.

Scientists from across the globe have tried to solve the mystery behind the rising lakes. Some think climate change is to blame, arguing that warming sea created more evaporation and clouds, which led to more rainfall. But if true, that would be strange, because in most of the world climate change is causing lakes to shrink.

The phenomenon is spur- ring calls for more research to help explain – and mitigate – the situation. Until scientists are able to identify the cause and work toward a solution, thousands of farmers on this Caribbean island will have to adapt.

The phenomenon is spur- ring calls for more research to help explain – and mitigate – the situation. Until scientists are able to identify the cause and work toward a solution, thousands of farmers on this Caribbean island will have to adapt.

This reporting was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Photo/JACOB KUSHNER

On a sunny hill overlooking a valley of shrubs, yellow grass and maize, Deodat Madembwe watches a team of masons make bricks for an elementary school he’s building.

As a young man growing up in central Tanzania, Madembwe too was a mason. Back then the most popular way to make bricks was to mould them loosely out of dirt and clay and then burn them in a tanuru – the Swahili word for a kiln. But to heat the kiln was to wreak havoc on the local environment.

“People cut trees to burn bricks,” he explained. To burn enough bricks for about five houses, they’d have to fell 10, even 20 trees. Burning the trees releases CO², contributing to climate change, and deforestation means there are fewer trees left to combat it. As Tanzania’s population grew, more and more houses arose and the landscape suffered. “We [were] making a desert,” said Madembwe.

But today, on a sunny plateau above Mbeya, the masonry unfolding before Madembwe’s eyes is of an entirely different breed. Two men with shovels quickly mix dirt they’ve sifted with a bit of sand and cement. They add water and shovel the mixture into a small steel device. A third man closes the heavy metal lid and pulls down hard on a long green lever. He releases, and a perfectly rectangular gray brick rises up.

NGOs, governments and local cooperatives have been experimenting with so-called compressed stabilised earth blocks (CSEB), a green alternative to tree-consuming burnt bricks, on a small scale for years. But they may soon rise to global prominence, prompted in part by interest from an unlikely party: the largest cement manufacturer in the world.

Read the full story at African Business Magazine via SparkNews. This article is part of a series of reports by Solutions&Co published to coincide with the COP21 Climate Talks in Paris.