A guide for journalists: How to report on human-wildlife conflict. Tips from the writers, editors and filmmakers who do it best.

solutions journalism

The Relentless Rise of Two Caribbean Lakes

National GeographicIn Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the lakes are flooding farmland, swallowing communities and leading to deforestation, baffling climate scientists.

Jacob Kushner

Story and photos by Jacob Kushner for National Geographic

The Chinese Company Eradicating Malaria in Africa

The AtlanticIn 2007, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation announced an ambitious endeavor: To eradicate malaria across the globe.

It was late to the game. That year, Chinese scientists working with a Chinese philanthropist had already begun eradicating malaria from the small African nation of Comoros. Now they’re setting their sights on a more ambitious location: Kenya, the East African nation of nearly 50 million people.

Read: The Atlantic

Listen: The China Africa Podcast

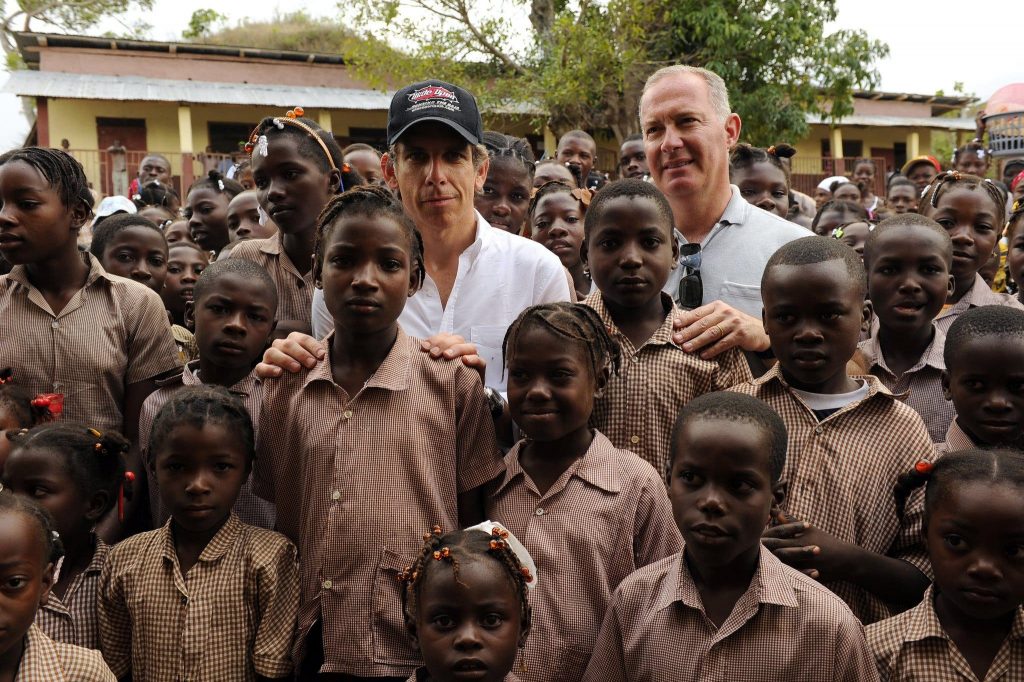

The Voluntourist’s Dilemma

New York Times Magazine

Photo: Ben Stiller visiting Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in April 2010 as part of a school-rebuilding project in which he was involved. Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images

Each year, 1.6 million voluntourists descend upon the Haitis of the world.

Read: The New York Times Magazine

Resurrection Science

WIREDBiologists Could Soon Resurrect Extinct Species. But Should They?

“Until we make space for other species on Earth, it won’t matter how many animals we resurrect,” writes M.R. O’Connor in her book Resurrection Science. “There won’t be many places left for them to exist.”

“Paradoxically, the more we intervene to save species, the less wild they often become.”

Read: WIRED

Railway Splits Kenya’s Parks, Threatens Wildlife

National GeographicAs dawn breaks, nine Kenya Wildlife Service rangers dressed in camouflage and brandishing rifles assemble at an airstrip. They are equipped with a Cessna, a helicopter, and a caravan of Toyota Land Cruisers. Their mission: find, tranquilize, and collar Tsavo’s savanna elephants to see how well they traverse a new rail line that has recently split their habitat in two. It is the first time in history that elephants are being collared specifically to study how they interact with human infrastructure.

Scientists hope a new vaccine will reduce malaria in Africa. But is it worth the cost?

National Geographic‘They paid a guy to kill me’

The GuardianIn Uganda, a lesbian activist helps straight people fight stigma of a disease once thought of as ‘gay.’

Read: The Guardian

On the run from the armed cattle rustlers of rural Kenya

The GuardianIn Kenya’s Baringo County, police reservists are tasked with carrying out the work that Kenya’s real police and armed forces have been unable or unwilling to do: fighting off armed bandits who are terrorizing parts of central Kenya as they steal livestock and shoot anyone who gets in their way.

Read: The Guardian

Haiti farmers eager to receive compensation after ‘groundbreaking’ land deal

Reuters PLACE

Farmer Remy Augustin, 54, prepares the ground to plant maize on a plot owned by his niece near Caracol, Haiti, December 10, 2019. Handout by Allison Shelley

A decade after an earthquake killed more than 200,000 people, farmers in Haiti are waiting to receive compensation for their land used to build an industrial park. Located in Haiti’s northern region, the $300 million Caracol Industrial Park opened in 2012 and now employs approximately 15,000 people, most of whom work in clothing factories there.

In 2018, farmers who had been evicted from their land in 2011 struck a rare deal with the IDB to provide Caracol’s 100 most vulnerable families with new, titled land.

Read the full story at the Thompson Reuters Foundation (PLACE). Reporting supported by The Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting.

When Traditional Reporting Isn’t Enough (argument)

Overseas Press Club of America

“Solutions journalism” is built around understanding not just what’s failing, but also what is working–and why. Too often we report singularly on problems without taking the time to explain when viable solutions to them exist. Solutions journalism doesn’t argue against covering abuses of power, conflict or corruption. It merely asserts that unless we also shed light on potential solutions to those problems, we haven’t quite finished the job.

Read my piece on the importance of Solutions Journalism in international reporting in Dateline, the magazine of the Overseas Press Club of America. Learn more at SolutionsJournalism.org

Gay-Rights Activists Hoping for a Legal Victory in Kenya

The New Yorker

Simon Maina

Kenya’s penal code punishes acts “against the order of nature”—usually interpreted as sex between men—with up to fourteen years in prison. It also prescribes up to five years in prison for “gross indecency with another male person,” which is often interpreted as other, undefined sexual acts between men. Worldwide, at least seventy nations—more than a third of all countries—still outlaw homosexuality, and it remains illegal in more than thirty of the fifty-four African countries.

L.G.B.T. activists in Kenya are taking on these laws. Changing a society’s values would take generations, they reasoned, but striking down an unjust law could be accomplished in just a few years. Read: The New Yorker

An Ungoverned City

U.S. News & World ReportCan cities function without a government? In Canaan, Haiti, residents give it a try.

Nine years ago, Canaan 1 was little more than a nameless, hilly swath of land patchworked by boulders and cinder blocks marking where people hoped to one day see proper houses, a hospital, a school, a police station and a basketball court.

Today, the neighborhood is one of many rapidly expanding areas of Canaan, Haiti’s newest city – named for the biblical promised land – home to between 280,000 and 320,000 people.

“We wanted to show the state who we are – that we can put down more than just one or two dollars here,” says Evenson Louis.

Read: U.S. News & World Report

Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Uganda Attempts to Shut Down Controversial Silicon Valley-Funded Schools

Columbia Global Reports

School children in Malindi, Kenya, February 2018. Photo by Ian Ingalula, Creative Commons.

Bridge International Academies was conceived in 2007 to be the McDonald’s of global education, promising to better educate poor students using Nooks and standardized curriculums for as little as $6 to $7 a month. Using tablets and standardized curriculums in each country, Bridge operates more than 520 schools, teaching some 100,000 students in Uganda, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria and India. It’s currently expanding in Asia with dreams of reaching an ambitious 10 million students across the world by 2025.

But Some African parents may be uneasy about the idea of a western-conceived company disrupting something they hold so dear: control over their children’s education. Bridge threatens to globalize—or perhaps, to westernize—the sector on which many Africans bank their families’ futures.

Read the full story at Columbia Global Reports.

Nudging in Nairobi

U.S. News & World ReportAn emerging science is helping Kenyans make smarter decisions about bargaining, sanitation and more.

Last year at primary schools in western Kenya, social scientists were busy performing dirty skits in front of hundreds of children. The script went like this:

Last year at primary schools in western Kenya, social scientists were busy performing dirty skits in front of hundreds of children. The script went like this:

The facilitator pretends to go to the bathroom behind a tree, then wipes using a thin leaf or piece of paper. But the leaf or paper rips, and she reacts with surprise upon getting (imaginary) feces on her hand. But she doesn’t wash her hands. Instead she wipes them on her clothes, then goes to shake the hand of one of the students, or picks up a mandazi – a doughnut – and offers it to a student to eat.

The students recoil in disgust, and the facilitator’s work is done: She has just implanted a “disgust trigger” into the kids’ brains – a simple, but powerful psychological reminder that forgetting to wash your hands is gross. And it works.

Welcome to behavioral psychology, the emerging science that seeks to nudge people to make smarter decisions.

Read the full story at U.S. News & World Report.