In Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the lakes are flooding farmland, swallowing communities and leading to deforestation, baffling climate scientists.

Jacob Kushner

Story and photos by Jacob Kushner for National Geographic

In Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the lakes are flooding farmland, swallowing communities and leading to deforestation, baffling climate scientists.

Jacob Kushner

Story and photos by Jacob Kushner for National Geographic

Biologists Could Soon Resurrect Extinct Species. But Should They?

“Until we make space for other species on Earth, it won’t matter how many animals we resurrect,” writes M.R. O’Connor in her book Resurrection Science. “There won’t be many places left for them to exist.”

“Paradoxically, the more we intervene to save species, the less wild they often become.”

Read: WIRED

As dawn breaks, nine Kenya Wildlife Service rangers dressed in camouflage and brandishing rifles assemble at an airstrip. They are equipped with a Cessna, a helicopter, and a caravan of Toyota Land Cruisers. Their mission: find, tranquilize, and collar Tsavo’s savanna elephants to see how well they traverse a new rail line that has recently split their habitat in two. It is the first time in history that elephants are being collared specifically to study how they interact with human infrastructure.

Cornelius said the drive to Arabal would take an hour, but it’s been more like three. Already a full day’s journey from Nairobi, we chanced that by dark we could reach the Arabal river and make it back to the town of Marigat to sleep. But now the sun is inching westward and our car is running out of gas.

This isn’t a place you want to be stranded for the night. Baringo County is in the midst of a war over livestock. A severe drought has forced Pokot herders to drive their cows and goats from the dry flatlands up into the beautiful mountains above Lake Baringo in search of grass. But this land is inhabited by Tugen, and the Tugen are struggling to feed their own livestock as it is.

In central Kenya, grass and vegetation can be a matter of life and death, and not just for the animals. Pastoralists depend upon milk and meat for their livelihoods. Deprived of that income, entire communities can become food insecure. For many families, livestock are their only assets: they have no bank accounts, no land to farm.

Combine those stakes with the fact that experts believe there are 530,000 to 680,000 guns in circulation among civilians in Kenya. Guns have long been traded across Kenya’s porous border with Somalia, but some have recently been traced to Uganda and South Sudan. Most herders who carry them do so for self-defense—to protect their animals from raiders. But others use them to raid.

Some of the Pokot who have crossed into the administrative region of Arabal this year fall into the latter category. Since the drought began late last year, there have been dozens of shootouts between Tugen, Pokot, and the police. Thousands of heads of livestock have been stolen, though just how many thousands is anyone’s guess.

Survivors of these shootouts speak of the Pokot as if they were immune to bullets, as if they were sharpshooters who never missed, as if their ammunition were infinite. But survivors are hard to find.

Read the feature story at Roads & Kingdoms. Reported with Anthony Langat, photos by Will Swanson.

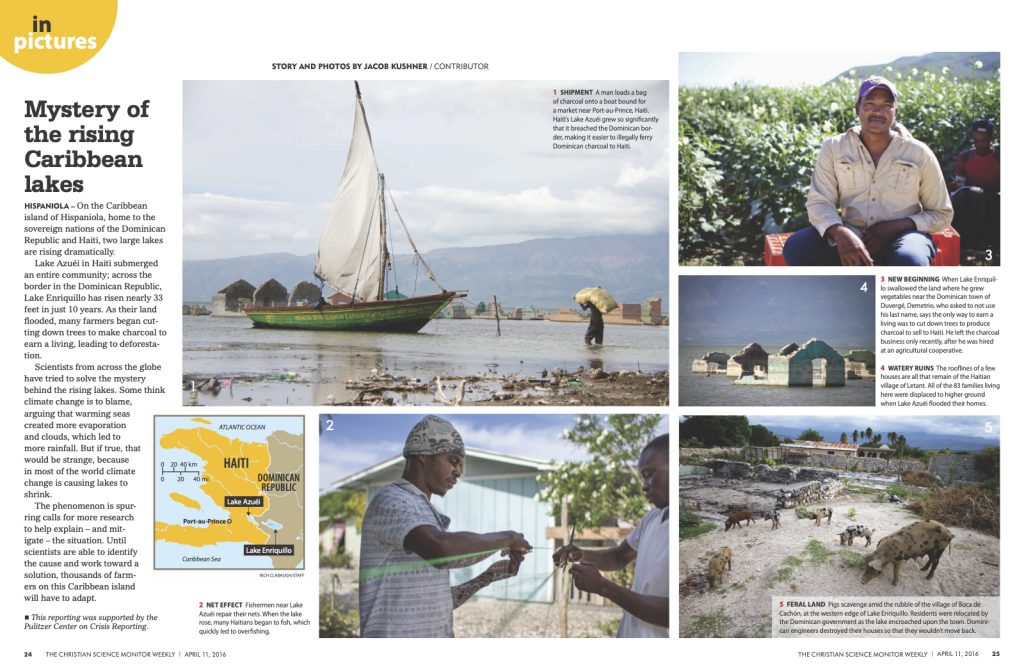

HISPANIOLA – On the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, home to the sovereign nations of the Dominican Republic and Haiti, two large lakes are rising dramatically.

Lake Azuéi in Haiti submerged an entire community; across the border in the Dominican Republic, Lake Enriquillo has risen nearly 33 feet in just 10 years. As their land flooded, many farmers began cut-ting down trees to make charcoal to earn a living, leading to deforestation.

Scientists from across the globe have tried to solve the mystery behind the rising lakes. Some think climate change is to blame, arguing that warming sea created more evaporation and clouds, which led to more rainfall. But if true, that would be strange, because in most of the world climate change is causing lakes to shrink.

The phenomenon is spur- ring calls for more research to help explain – and mitigate – the situation. Until scientists are able to identify the cause and work toward a solution, thousands of farmers on this Caribbean island will have to adapt.

The phenomenon is spur- ring calls for more research to help explain – and mitigate – the situation. Until scientists are able to identify the cause and work toward a solution, thousands of farmers on this Caribbean island will have to adapt.

This reporting was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

A Kenya Wildlife Service ranger shoots Mohawk lion after he injured a person. Mohwak left Nairobi National Park and wandered south into the town of Isinya.

PHOTOGRAPH BY AFP/GETTY

NAIROBI, KENYA — First, a lioness ventured into the city as a decoy to draw officials away from her cubs that were lost in an army barracks.

Then, just weeks later, a pride of six lions breeched a fence into a pasture killing as many as 120 goats and sheep. One lion lost his bearings and ended up on a major highway, injuring a man before finding his way back into Nairobi National Park, located adjacent to Kenya’s capital city.

Now, this week, a popular lion named Mohawk ventured some 20 miles (32 kilometers) south of that park only to be surrounded and harassed by onlookers. When he responded by attacking one of them, he was shot and killed by park rangers.

Why are so many lions leaving Nairobi National Park? Read the full story at National Geographic

Photo/JACOB KUSHNER

On a sunny hill overlooking a valley of shrubs, yellow grass and maize, Deodat Madembwe watches a team of masons make bricks for an elementary school he’s building.

As a young man growing up in central Tanzania, Madembwe too was a mason. Back then the most popular way to make bricks was to mould them loosely out of dirt and clay and then burn them in a tanuru – the Swahili word for a kiln. But to heat the kiln was to wreak havoc on the local environment.

“People cut trees to burn bricks,” he explained. To burn enough bricks for about five houses, they’d have to fell 10, even 20 trees. Burning the trees releases CO², contributing to climate change, and deforestation means there are fewer trees left to combat it. As Tanzania’s population grew, more and more houses arose and the landscape suffered. “We [were] making a desert,” said Madembwe.

But today, on a sunny plateau above Mbeya, the masonry unfolding before Madembwe’s eyes is of an entirely different breed. Two men with shovels quickly mix dirt they’ve sifted with a bit of sand and cement. They add water and shovel the mixture into a small steel device. A third man closes the heavy metal lid and pulls down hard on a long green lever. He releases, and a perfectly rectangular gray brick rises up.

NGOs, governments and local cooperatives have been experimenting with so-called compressed stabilised earth blocks (CSEB), a green alternative to tree-consuming burnt bricks, on a small scale for years. But they may soon rise to global prominence, prompted in part by interest from an unlikely party: the largest cement manufacturer in the world.

Read the full story at African Business Magazine via SparkNews. This article is part of a series of reports by Solutions&Co published to coincide with the COP21 Climate Talks in Paris.

Elias Kimaiyo says the Kenya Forest Service has burned down his home repeatedly as part of a push to evict him and other members of the Senger, an indigenous tribe, from the forests where they have lived for generations. “Most of the time,” Kimaiyo says, “I just live in fear.” / TONY KARUMBA

Another chapter in the World Bank’s fraught relationship with indigenous peoples who live on or near land targeted for development.

By Jacob Kushner, Anthony Langat, Michael Hudson and Sasha Chavkin

It was a morning routine: Elias Kimaiyo woke up, went outside his family’s mud-and-thatch home and climbed a hill. His goal: see where Kenya Forest Service officers were heading that day as they trudged into the forest from a nearby ranger station. Like thousands of his fellow tribespeople, he spent many of his days worrying about whether his family would be the next to be evicted by gun-toting rangers.

One morning in late 2011, Kimaiyo saw that KFS officers were heading in another direction. He went home and worked with his wife, Janet, harvesting their small corn crop in a clearing in the forest. In the afternoon, he decided to check again.

This time, when he climbed the hill, he could see a group of rangers heading toward his house. Kimaiyo ran home. He and his wife began grabbing their things—blankets, utensils, a mattress—and hiding them in the brush. They could see their neighbors’ homes burning. Kimaiyo’s one-year-old son sat in the dirt, crying, as his mom and dad carried armfuls of their belongings deeper into the forest.

Kimaiyo and his wife fled with their son to the other side of a river. They hoped the KFS officers would somehow miss their house in the dense forest.

They didn’t.

Kimaiyo watched, he says, as flames consumed his house and what was left inside—tables, chairs, the bed frame, even the mattress, which the rangers had discovered poorly hidden in the brush and tossed onto the fire.

It was the fourth time, Kimaiyo claims, that Kenya’s government had destroyed his home since the 2007 launch of a forest conservation project that the World Bank said would “improve the livelihoods of communities participating in the co-management of water and forests.”

Read the full ICIJ investigation.

This is the latest installment of “Evicted and Abandoned,” an examination of the hidden toll of development financed by the World Bank. The project is a collaboration between the ICIJ and The Huffington Post, with contributions from journalists around the globe. The story also appeared at The Huffington Post and PRI’s The World.

By Jacob Kushner, Anthony Langat, Sasha Chavkin and Michael Hudson

Gladys Chepkemoi was weeding potatoes in her garden the day the men came to burn down her house.

After her mother-in-law told her that rangers from the Kenya Forest Service were on their way, Chepkemoi strapped her 1-year-old son on her back and hurried to her thatched-roofed home. She grabbed two tins of corn, blankets, plates and cooking pans, and hid in a thicket.

She watched, she said, as the green-uniformed rangers set her house ablaze.

After they were gone, she came out of the thicket to see what was left.

“What used to be my home was now ashes,” she said.

The young mother is one of thousands of Kenyans who have been forced out of their homes since the launch of a World Bank-financed forest conservation program in western Kenya’s Cherangani Hills. Human rights advocates claim government authorities have used the project as a vehicle for pushing indigenous peoples out of their ancestral forests.

They are not alone.

In developing countries around the globe, forest dwellers, poor villagers and other vulnerable populations claim the World Bank — the planet’s oldest and most powerful development lender — has left a trail of misery.

Read the full ICIJ investigation.

This is the latest installment of “Evicted and Abandoned,” an examination of the hidden toll of development financed by the World Bank. The project is a collaboration between the ICIJ and The Huffington Post, with contributions from journalists around the globe. The story also appeared at The Huffington Post and PRI’s The World.

UPDATE: This investigation won the 2015 Online News Association Award for Investigative Journalism.