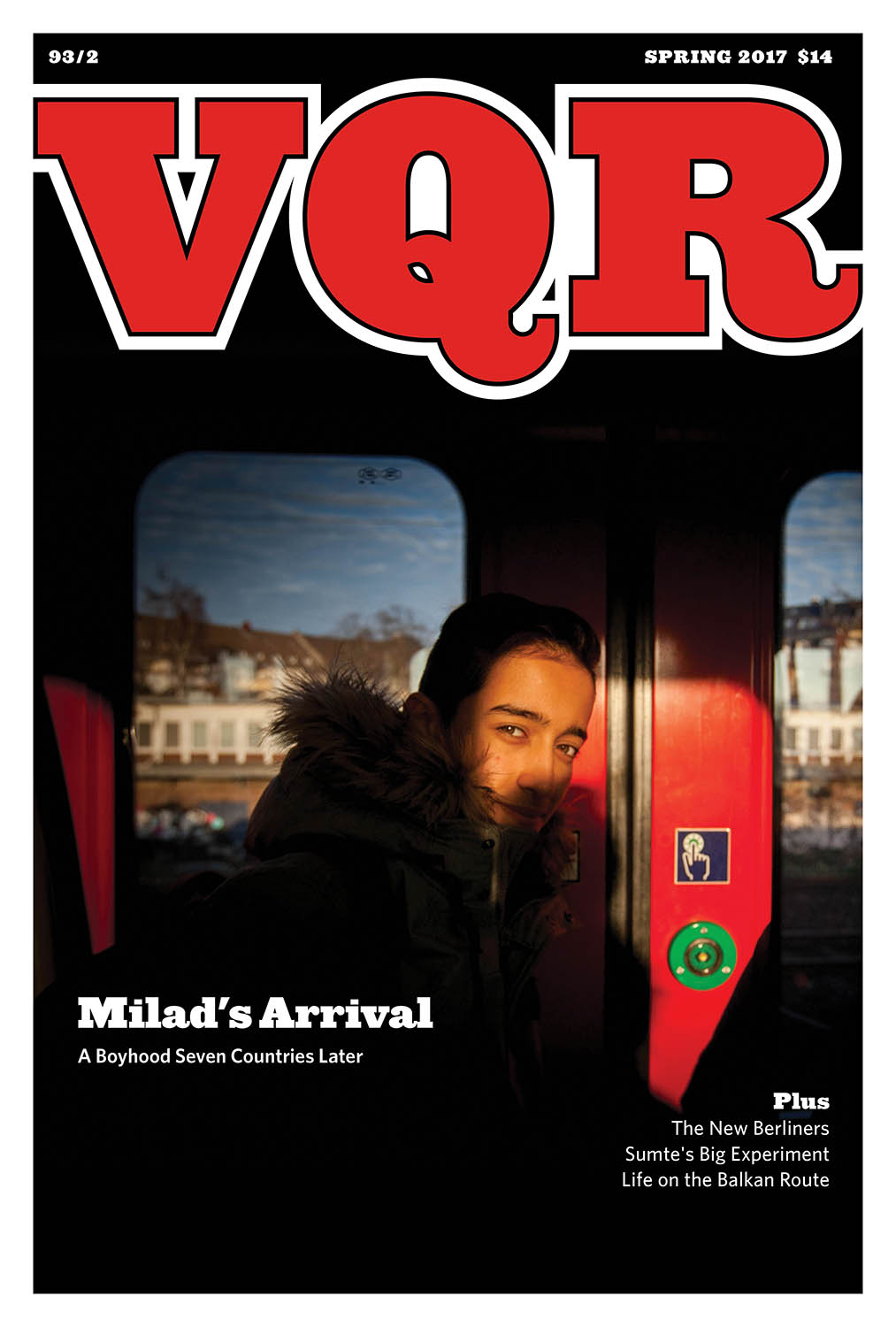

A ferry arrives at the wharf in Anse-a-Galets on the island of La Gonave, Haiti. /Jacob Kushner

Thousands sought refuge on the island of La Gonave four years ago. But little help ever arrived, something permanent residents know all too well.

ANSE-A-GALETS, Haiti — To traverse the 13-mile stretch of Caribbean Sea to the island of La Gonave, one must choose between three types of boats, none particularly safe.

louis vuitton bucket

First there are the “fly boats,” speed boats with outboard motors that race a dozen people from one side to the other. From time to time they flip over. Few records exist as to how many people survive.

Then there are the two large steel ferries that carry a few hundred passengers slowly across the sea each day. In 1997, one of those ferries sank, killing 200.

nike air max infrared

Last, there are the sailboats — wooden ships built from hand-carved lumber and pieced together with hammered nails. Their canvas masts are reminiscent of those in the “Pirates of the Caribbean” movie franchise. They carry everything from rice to dry cement, motorcycles, cars and trucks.

In better times, Haitians travel to and from the 300-square-mile island as a matter of routine, however risky. In times of emergency, like the massive earthquake of four years ago, they come to La Gonave in droves.

In the first 19 days after the earthquake, 630,000 people fled Port-au-Prince, 7,500 of them to La Gonave, according to a 2011 study. Untold thousands more fled there from other earthquake-affected areas. Some NGOs put the total at 20,000, which would mean the island’s normal population of approximately 100,000 increased by between 15 and 20 percent almost overnight.

coach imitation purses

To feed and house them all would have required a substantial amount of the $9 billion pledged by international governments for Haiti’s recovery. But little of that aid — or the aid allocated by private donors — reached the people of La Gonave, GlobalPost found. Most of the migrants returned to the mainland in the months after the earthquake, leaving permanent residents in a dire state.

Read the full story at GlobalPost.