More refugees live in cities. Could cash help them rebuild their lives?

Refugees

Love Thy Neighbor

The AtavistAmerican evangelicals’ antigay gospel forced him to flee Uganda. Then Christians in California offered him a home. A refugee’s story, in words and pictures.

Read: The Atavist

Birthright Denied

Moment Magazine

Story and photos by Jacob Kushner

The campaign to expel the children of Haitian immigrants in the Dominican Republic is impractical. Their labor—and that of their parents—helped propel the Dominican economy last year to grow faster than all but one other country’s in Latin America, firmly establishing it as a middle-class nation. They are a significant part of the workforce in the booming construction and tourism industries that have helped transform the Dominican Republic into the most popular travel destination in the Caribbean.

The campaign to expel the children of Haitian immigrants in the Dominican Republic is impractical. Their labor—and that of their parents—helped propel the Dominican economy last year to grow faster than all but one other country’s in Latin America, firmly establishing it as a middle-class nation. They are a significant part of the workforce in the booming construction and tourism industries that have helped transform the Dominican Republic into the most popular travel destination in the Caribbean.

But in a chaotic democracy that has adopted 38 different constitutions over a century and a half, anti-Haitianismo is the one enduring notion that mainstream parties across the political spectrum can invoke with impunity. It is driven by the fervor of Dominican nationalists, and, in particular, by one powerful, ultra-conservative family and its allies. Together, they are waging a political, legal and media war to defend the Dominican Republic against what they believe is the nation’s gravest threat: Haitian immigrants and their children.

Read: Moment Magazine

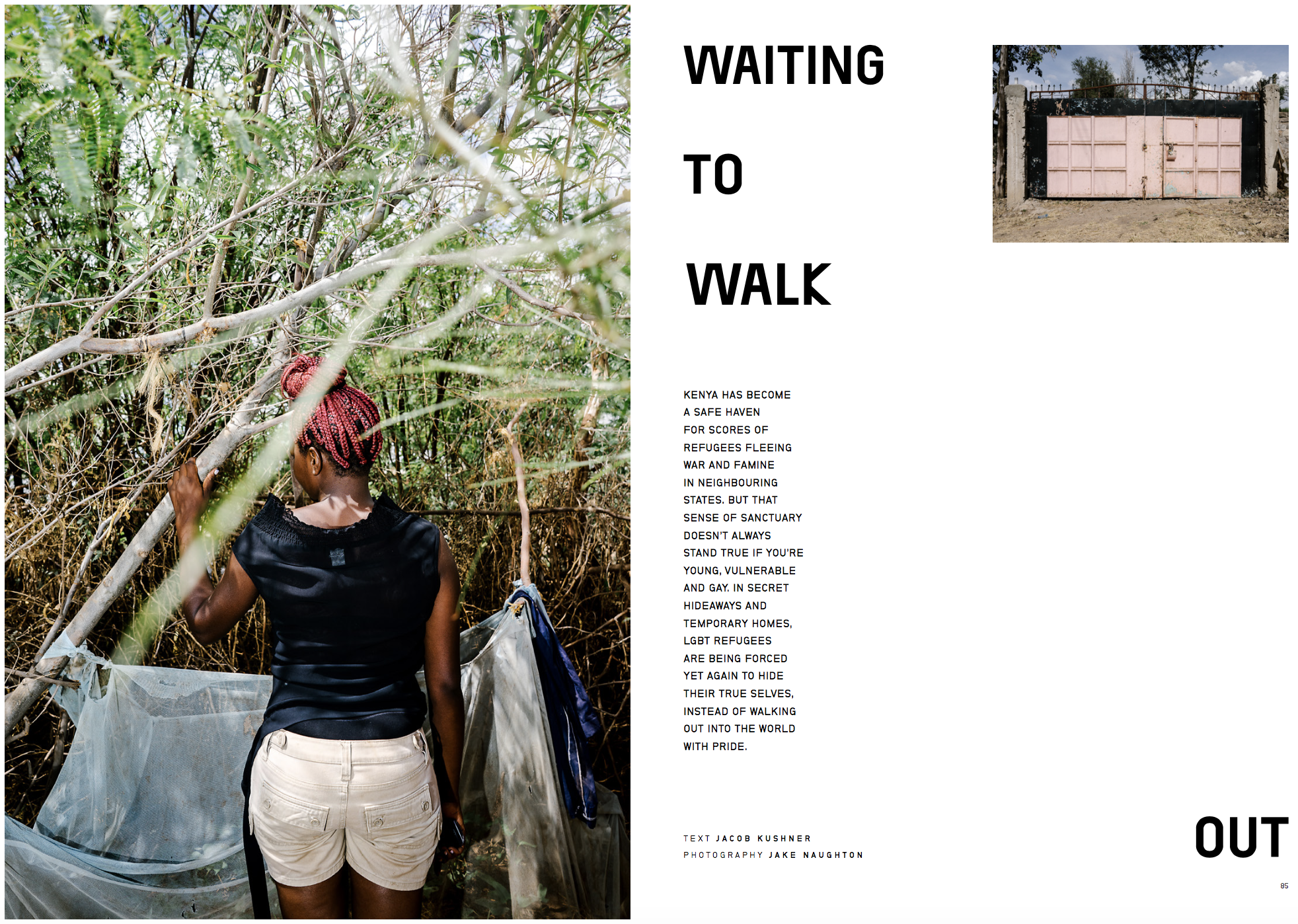

Waiting to Walk … Out.

HUCK MagazineKenya has become a safe haven for scores of refugees fleeing war and famine in neighboring countries. But that sense of sanctuary doesn’t always stand true if you’re young, vulnerable and gay. In secret hideaways and temporary homes, LGBT refugees are being forced yet again to hide their true selves.

Citizenship shift leaves Dominican-Haitians stateless (PBS Newshour)

PBS NewshourThe Dominican government made headlines when it ended birthright citizenship for children born in the D.R. To undocumented parents.

Watch the segment I field-produced, or read the full transcript, at PBS Newshour.

Permanent Displacement

Pacific Standard

/Jacob Kushner

Inside Kakuma, Kenya’s 25-Year-Old Refugee Camp

In 1992, the U.N. formally recognized Kakuma as a refugee camp — a temporary shelter. A quarter-century later, Kakuma hosts more than 150,000 refugees — victims of all manner of East African calamities, from Ugandan homophobia to political unrest in Burundi. Presently, it is filling up once again with people fleeing civil war in South Sudan.

Long before the Syrian civil war, before millions of people began fleeing to camps in Turkey, Jordan, and elsewhere in search of safety, Kakuma was something of an icon in the global refugee crisis. Today, it stands as a solemn reminder of the permanence of humanity’s displaced masses.

In Germany’s epicentre of anti-immigrant politics, a haven for refugees

Al Jazeera

Refugee youth partake in the international cafe’s theatre activities and perform skits based on their own experiences [Daniel Koch/Staatsschauspiel Dresden]

Here, immigrants tell stories about their homelands and laugh with German volunteers about cultural differences. Graffiti covers the walls, a sign on one wall reads, “Refugees welcome. Bring your families.”

They do. Children play table football, while teenagers – mostly boys – lounge on couches.

But this particular space, known as the “international cafe”, rests in an uncanny location.

Dresden, the capital of Saxony, is a stronghold for Germany’s anti-immigrant politics. Each week, thousands of supporters of the right-wing, anti-Muslim, anti-refugee movement PEGIDA gather to demonstrate against Germany’s liberal policies towards asylum seekers.

They chant that refugees should “go home” and denounce what they see as the Islamisation of Germany. Refugees often take care to avoid central Dresden on Monday nights out of fear they’ll become targets of the protesters’ angry speech, or worse.

Read the full story at Al Jazeera. This is the final story in a 7-part series.

Rejected asylum: From Karachi to Germany and back again

Al Jazeera

Jacob Kushner for Al Jazeera

A lawyer and his family fled death threats in Pakistan and came to Germany only to face terrorism. Now, they’re being forced to go home.

Salzhemmendorf, Germany – Late one summer night in this quiet village, a Molotov cocktail came flying through the window of the apartment where a Zimbabwean refugee and her three young children lived.

In the apartment next door, an asylum seeker from Pakistan who calls himself Mr Khan heard nothing. He was sitting at his computer with his headphones on, watching videos on the internet with news from Karachi. He and his family had fled Pakistan for Europe in 2012 after some of his colleagues – lawyers who were Shia Muslim – had been murdered by Sunni Islamic extremists.

When he heard a loud banging on his apartment door, he opened it to find a police officer, who ushered him and his family outside. The building smelled of smoke, and Khan surveyed the wreckage: The Molotov cocktail had destroyed the bedroom it was thrown into. It was the room in which the woman’s 11-year-old son usually slept on a mattress on the floor. By chance, he was sleeping in his mother’s room that night, which may have saved his life.

Outside, “I heard the sound of the fire brigade,” Khan said. “If they did not come, this whole building could have been finished.”

After Khan’s building was attacked by xenophobic Germans, he wondered whether Germany would accept their asylum applications, and allow them to stay.

“Tomorrow, I don’t know what will happen,” Khan said. “Maybe Germany will say, ‘Out!'”

In fact, it did.

Read the full story at Al Jazeera. This is the 6th article in a 7-part series.

When Refugees Are Terrorized By the German Right Wing

Columbia Global Reports

Photo by Arnaud333, Wikimedia Commons.

On December 7, 2015, two baby carriages were set on fire at an apartment complex housing refugees in the pristine Thuringia town of Altenburg. Ten refugees, including two infants, suffered from smoke inhalation. The attack came two days after right-wing protesters marched through the town carrying signs that read, “Please continue your flight. There’s nowhere to live here.”

“On the ground floor there was a woman living with her baby who had to jump out without shoes,” district administrator Michaele Sojka told me when I met her last June. “Everyone was really shocked that something like that could happen in our city.

Two men were arrested, and six months later one of them was found guilty of arson. The judge said the man had “acted on xenophobic motives.” The other was handed a fine for repeating Nazi slogans. “One of them must have been drunk that night,” Brit Krostewitz, a volunteer with the Altenburg Network for Integration, told me. “They are just stupid Nazis.” Most Germans know the type.

This is Germany, a country whose leaders just 80 years ago tried to deport and then exterminate all non-Christians and “outsiders.” A country so ashamed of its xenophobic past that to display any hint of nationalism, such as to wave a German flag during a soccer match, remained taboo. Germany, a liberal European state that goes so far as to limit speech—by criminalizing Holocaust denial—least anyone attempt to forget or manipulate that torrid past.

And yet, Germany has recently become a breeding ground for small pockets of xenophobic citizens to commit hate crimes and terrorism against foreigners.

Read the full story at Columbia Global Reports. This is the first part of a short series on refugees in Germany.

Escaping Aleppo only to encounter violence in Germany

Al Jazeera

Illustration by Jawahir Al-Naimi/Al Jazeera

In Freital, Abu Hamid and his fellow refugees were attacked by right-wing Germans, who could be convicted of terrorism.

Freital, Germany – On Halloween night, 2015, in this town outside the Saxon capital of Dresden, Abu Hamid went into the kitchen to grab some food when he noticed sparks of light outside the window. Sensing danger, he and his roommates rushed out of the kitchen just as a booming explosion shook the house, shattering the windows and sending pieces of glass into one man’s face.

“After that, we thought someone would come inside the home and attack us,” Abu Hamid said. “One of my friends, he took a knife.”

The explosion was caused by illegal fireworks, as they later discovered. It appeared someone had placed them on the windowsill that night to target those inside. For months beforehand, local police had failed to see a connection between a series of right-wing protests against refugee housing shelters and the bombing of a car belonging to a left-wing politician in Freital. Just one month before Abu Hamid’s apartment was attacked, another, almost identical firework attack had been launched on the house of some Eritrean refugees in the town.

It wasn’t until news outlets as far away as Berlin began pressuring authorities to take action that Germany’s federal prosecutor took up the case. In a dramatic SWAT-style raid, federal and state police arrested five suspects believed to have formed an organised anti-refugee militia.

Read the full story at Al Jazeera. This is the fifth story in a seven-part series.

Clausnitz: When a mob awaited refugees in a German town

Al Jazeera

A police car is parked in front of an asylum shelter in Clausnitz in March 2016 [Hannibal Hanschke/Reuters]

Once the face of anti-refugee sentiment in Germany, Clausnitz and its newcomers have learned to co-exist.

On a cold night last year, some 70 Germans, mostly men, surrounded a bus of refugees in this small town and began chanting at them to “go home”.

It was February 2016, and nearly one million asylum seekers had arrived the previous year to Germany from the Middle East, Africa and elsewhere. As they waited to see if they’d be allowed to stay, they were sent off to live in different cities and towns across the country.

One bus with 15 asylum seekers from Syria, Lebanon, Iran and Afghanistan was sent one evening to the village of Clausnitz, in the eastern German state of Saxony.

Their hostile reception by protesters who shouted at them and blocked them from entering their apartments made international headlines. A video of the encounter circulated widely, reinforcing stereotypes of small-town Germans as racist and blemishing Germany’s so-called “welcome culture”.

The refugees pleaded to the driver to turn around and return them to the temporary shelters they’d been living in around Dresden, the Saxon capital. Neither the refugees nor the demonstrators wanted this. But then, neither had a choice.

Read the full story at Al Jazeera. This is the 4th story in a 7-part series.

The forgotten murder of a 4-year-old refugee in Berlin

Al Jazeera

Refugees wait outside the State Office of Health and Social Affairs in the early hours of December 9, 2015 [Sean Gallup/Getty Images]

At the start of the refugee crisis, dysfunction and danger awaited those registering for asylum in Germany.

Before the wheels of Germany’s asylum system were fully turning, hundreds of thousands of newly arrived refugees were piling up in cities throughout the country. In Berlin, tens of thousands were forced to sleep on the streets at night and fight for their place in line by day at the now-infamous Lageso , the State Office of Health and Social Affairs, while they waited to apply for asylum.

The climate of fear and tension at Lageso reached its climax one afternoon in October 2015 when a 32-year-old German man appeared at Lageso and, in the chaos of the crowds, enticed a four-year-old Bosnian boy named Mohamed away from his family and abducted him.

The climate of fear and tension at Lageso reached its climax one afternoon in October 2015 when a 32-year-old German man appeared at Lageso and, in the chaos of the crowds, enticed a four-year-old Bosnian boy named Mohamed away from his family and abducted him.

Read the full story at Al Jazeera. This is the 3rd story in a 7-part series.

Revisiting Germany’s Rostock Riots–the most disturbing resurgence of xenophobic violence since Nazism

Al Jazeera

Right-wing extremists run through spray from water cannons during clashes between police and demonstrators in Rostock, Germany, on Monday, August 24, 1992 [Thomas Haentzschel/AP]

In the quarter of a century since, many foreigners arriving in Germany have experienced the warmest of welcomes – but a few have experienced chilling acts of hatred. This series explores how a small minority of ultra-xenophobic Germans has tarnished their nation’s reputation as a haven for the world’s displaced masses. These stories are primarily told through the experiences of immigrants and asylum seekers who survived xenophobic harassment or attacks.

Their stories are the exception to the norm: incidents of violent xenophobia are rare in Germany compared with other countries. Indeed, Germany has welcomed more asylum seekers in recent years than any other European nation – the United Kingdom, France, Poland, Austria, Hungary, and magnitudes more than the far more populous United States. When faced with the largest exodus of people since World War II, none of these nations welcomed refugees as unconditionally as Germany did. It’s precisely because of this reputation that Al Jazeera is taking a hard look at what happens on the occasions when that welcome culture goes awry.

Their stories are the exception to the norm: incidents of violent xenophobia are rare in Germany compared with other countries. Indeed, Germany has welcomed more asylum seekers in recent years than any other European nation – the United Kingdom, France, Poland, Austria, Hungary, and magnitudes more than the far more populous United States. When faced with the largest exodus of people since World War II, none of these nations welcomed refugees as unconditionally as Germany did. It’s precisely because of this reputation that Al Jazeera is taking a hard look at what happens on the occasions when that welcome culture goes awry.

This is the first story in a 7-part series. Read it at Al Jazeera.

Story 2: Ibraimo Alberto, a Mozambican immigrant and child of former slaves, encountered many opportunities in Germany. But he also experienced racism, big and small, in the east and west– including the murder of a friend. Read his story at Al Jazeera.

Story 3: The climate of fear and tension among more recent refugees arriving to Germany reached a climax one afternoon in October 2015 when a 32-year-old German man enticed a four-year-old Bosnian boy named Mohamed away from his family and abducted him. Read the story at Al Jazeera.

Story 4: On a cold night last year, some 70 Germans, mostly men, surrounded a bus of refugees in the small town of Clausnitz and chanted at them to “go home”. On the bus were 15 asylum seekers from Syria, Lebanon, Iran and Afghanistan. Their hostile reception by protesters who blocked their path made international headlines, reinforcing stereotypes of small-town Germans as racist and blemishing Germany’s so-called “welcome culture.” Neither the refugees nor the demonstrators wanted this. But then, neither had a choice. Read the story at Al Jazeera.

Story 5: On Halloween night, Abu Hamid went into the kitchen to grab some food when he noticed sparks of light outside the window. Sensing danger, he and his roommates rushed out of the kitchen just as a booming explosion shook the house, shattering the windows and sending pieces of glass into one man’s face. Local police had failed to see a connection between a series of right-wing protests against refugee housing shelters. It wasn’t until news outlets as far away as Berlin began pressuring authorities to take action that Germany’s federal prosecutor took up the case. In a dramatic SWAT-style raid, federal and state police arrested five suspects believed to have formed an organised anti-refugee militia. Read the story, Escaping Aleppo only to encounter terrorism in Germany, at Al Jazeera.

Story 6: A lawyer and his family fled death threats in Pakistan, so they flee to Germany for safety. Instead, their building is attacked–firebombed–by right-wing Germans. Khan wondered whether Germany would accept their asylum applications, and allow them to stay. “Tomorrow, I don’t know what will happen,” Khan said. “Maybe Germany will say, ‘Out!'” In fact, it did. Read the full story at Al Jazeera.

Story 7: Each week in Dresden, a group of refugees and Germans gather at a nondescript cafe hidden from view, pushed back from the street. The cafe provides a safe space for them to mingle with the locals to chat, practise their language skills, and sip tea and juice. It’s one of many spaces that have popped up across Germany to welcome refugees, help them with their asylum applications, teach them German, or just for engagement.

But this particular space, known as the “international cafe”, rests in an uncanny location. Dresden, the capital of Saxony, is a stronghold for Germany’s anti-immigrant politics. Each week, thousands of protestors chant that refugees should “go home” and denounce what they see as the Islamisation of Germany. Read the full story at Al Jazeera.

35 years as a Mozambican immigrant in Germany

Al Jazeera

Ibraimo Alberto was born to former slaves in Mozambique when it was still a Portuguese colony. His parents worried he would be forced into slavery when he went to Germany [Jacob Kushner/Al Jazeera]

In the quarter of a century since, many foreigners arriving in Germany have experienced the warmest of welcomes – but a few have experienced chilling acts of hatred. This series explores how a small minority of ultra-xenophobic Germans has tarnished their nation’s reputation as a haven for the world’s displaced masses. These stories are primarily told through the experiences of immigrants and asylum seekers who survived xenophobic harassment or attacks.

Their stories are the exception to the norm: incidents of violent xenophobia are rare in Germany compared with other countries. Indeed, Germany has welcomed more asylum seekers in recent years than any other European nation – the United Kingdom, France, Poland, Austria, Hungary, and magnitudes more than the far more populous

United States. When faced with the largest exodus of people since World War II, none of these nations welcomed refugees as unconditionally as Germany did. It’s precisely because of this reputation that Al Jazeera is taking a hard look at what happens on the occasions when that welcome culture goes awry.

A child of former slaves, Ibraimo Ibraimo Alberto, a Mozambican immigrant, encountered many opportunities, but also experienced racism, big and small, in the east and west– including the murder of a friend. Read his story at Al Jazeera. This is the 2nd story in a seven-part series.

In a World of Closed Borders, Deciding Who Deserves Asylum

The Nation & The Nation Institute Investigative Fund

Fenced in: Some refugees at Kakuma are segregated for special protection. /Jake Naughton

At Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya, workers face few humane options

From Turkey to Pakistan, from Iran to Ethiopia, refugee workers are being forced to make painful choices regarding the future of more than 21 million refugees, part of a record 65 million displaced persons around the world. They must choose between political and economic refugees, individuals and families, the healthy and the sick, the elderly and unaccompanied children, gay and straight. They try to move those most in need of help to the front of the line for resettlement somewhere safe.

But when it comes to triaging the world’s humanitarian crises, there are few humane choices.

Read in the February 27, 2017 edition of The Nation Magazine.