/JACOB KUSHNER

NAIROBI, Kenya — On a sunny afternoon in Nairobi, 37-year-old Francis Raymond Adika climbs into the front seat of a matatu, or public transit van, and slides next to the driver.

“I lost my brother in an accident,” says Adika. On August 15, 2001, a matatu was speeding down the wrong side of a two-lane road in Nairobi trying to pass traffic. When it swerved back into the correct lane it slammed headfirst into a truck. Adika discovered his brother’s body in the Nairobi morgue. He was 19, just days away from his high school graduation.

A Jesuit missionary who travels extensively across Africa, Adika says it isn’t just in Kenya where people lose their lives to reckless driving. “I lived in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Zambia – the carnage was just the same.”

Each year, 1.24 million people die in road accidents worldwide. By 2030 that number is expected to triple to 3.6 million, making road deaths the fifth-largest cause of death in the developing world – worse than AIDS or even malaria, according to the World Health Organization. Africa is the hardest hit, with 26 road deaths for every 100,000 people – nearly 50 percent above the global average.

But a series of scientifically rigorous, randomized control studies by Georgetown University may have found a simple way to dramatically reduce deaths on East African roads. By placing stickers inside buses and matatus that encouraged passengers to tell their driver to slow down, researchers discovered that the number of insurance claims fell by half for long-distance vehicles and by one-third overall.

Read the full article at U.S. News & World Report.

nerate solid evidence of progress to show funders.

nerate solid evidence of progress to show funders.

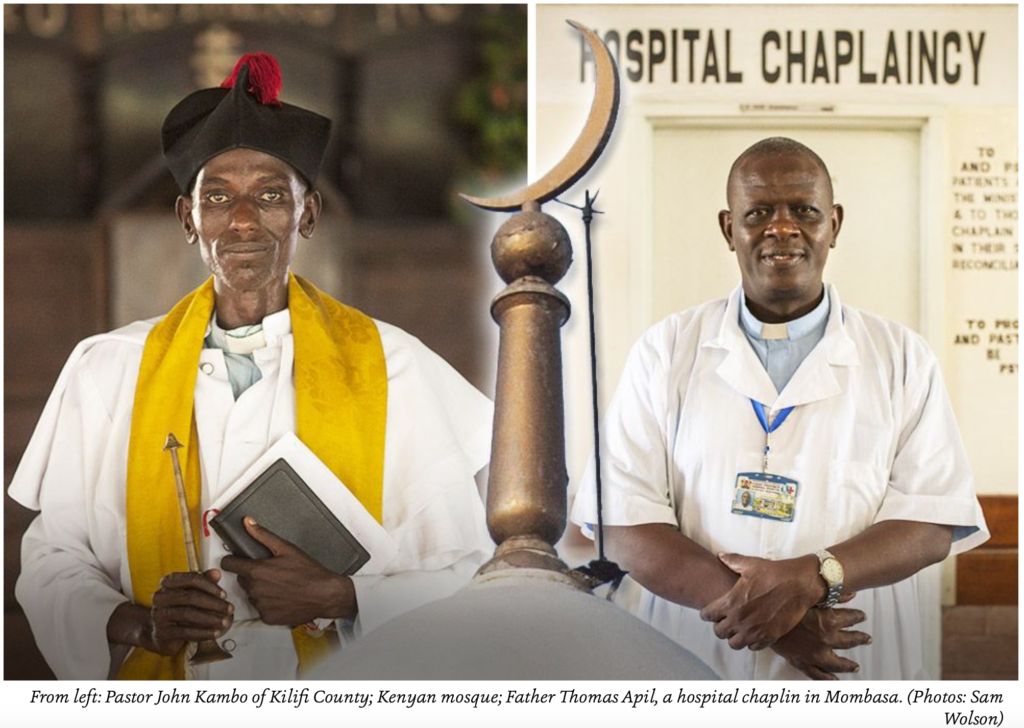

In an attempt to counter the anti-LGBT fervor gaining hold on Kenya’s coast, one gay rights organization has developed a new approach. Rather than confronting the religious leaders behind it, it’s inviting them to tea.

In an attempt to counter the anti-LGBT fervor gaining hold on Kenya’s coast, one gay rights organization has developed a new approach. Rather than confronting the religious leaders behind it, it’s inviting them to tea.