Christopher Furlong/Getty

In a nation known for minerals, a controversial crop is on the rise.

Before he started growing weed, Koti spent his days digging holes and tunnels, mining for morsels of gold. He would smoke weed — or bangias he calls it — to overcome his fear of the darkness that he faced underground. As a teen, he saw a tunnel collapse, trapping five fellow miners — only one was rescued. “It’s dangerous,” says Koti, of the illegal minerals trade that many eastern Congolese families depend on. “People were dying.”

The tragedy frightened him, but with no other source of income, he was back at the mine the next day. Then, in 2007, a foreign mining company kicked Koti and the other small-time miners off the land. With no other job, he bought cannabis seeds from a neighbor, planted them and, six months later, harvested a crop of cannabis that measured in the kilos. “I had no other job,” says Koti, who asked that his real name be withheld out of fear of authorities. “So I decided to start growing marijuana.”

The Democratic Republic of Congo, Africa’s second-largest nation by area, is known for nefarious trade in copper, coltan, cobalt, tin and other minerals. But now, tens of thousands of Congolese like Koti are setting their sights on a different sort of illegal resource: cannabis. The United Nations estimates that Africa produces 10,500 metric tons of cannabis — a fourth of all the marijuana in the world. Between 27 million and 53 million Africans use the drug, making up about one-fourth of all weed users worldwide.

But while cannabis farming comes without the physical fears that accompany mining, it carries its own share of risks, wrapped in politics from across the Atlantic. Decades of U.S. and international pressure are a key reason why cannabis cultivation is illegal in Congo. In 1961, the U.S. voted in favor of the U.N. Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which added marijuana to the list of drugs that were banned internationally. The way to solve America’s drug “problem” was by pinching off the global supply, or so the thinking went.

Farmers can’t receive international aid to grow an illegal crop. It also leaves them vulnerable to harassment from corrupt police officials.

The penalization of cannabis in Congo is endorsed by the U.S. at a time when many states are decriminalizing the drug at home. In Afghanistan, the U.S. has funded “alternative livelihood” programs to shift Afghan farmers away from cannabis. And in 2005, the U.S. vetoed an international attempt to “reschedule” cannabis as a less dangerous substance — a move that could have opened the doors to deregulation.

The penalization of cannabis in Congo is endorsed by the U.S. at a time when many states are decriminalizing the drug at home. In Afghanistan, the U.S. has funded “alternative livelihood” programs to shift Afghan farmers away from cannabis. And in 2005, the U.S. vetoed an international attempt to “reschedule” cannabis as a less dangerous substance — a move that could have opened the doors to deregulation.

Read the full feature at OZY.

The penalization of cannabis in Congo is endorsed by the U.S. at a time when many states are decriminalizing the drug at home. In Afghanistan, the U.S. has funded “alternative livelihood” programs to shift Afghan farmers away from cannabis. And in 2005, the U.S. vetoed an international attempt to “reschedule” cannabis as a less dangerous substance — a move that could have opened the doors to deregulation.

The penalization of cannabis in Congo is endorsed by the U.S. at a time when many states are decriminalizing the drug at home. In Afghanistan, the U.S. has funded “alternative livelihood” programs to shift Afghan farmers away from cannabis. And in 2005, the U.S. vetoed an international attempt to “reschedule” cannabis as a less dangerous substance — a move that could have opened the doors to deregulation.

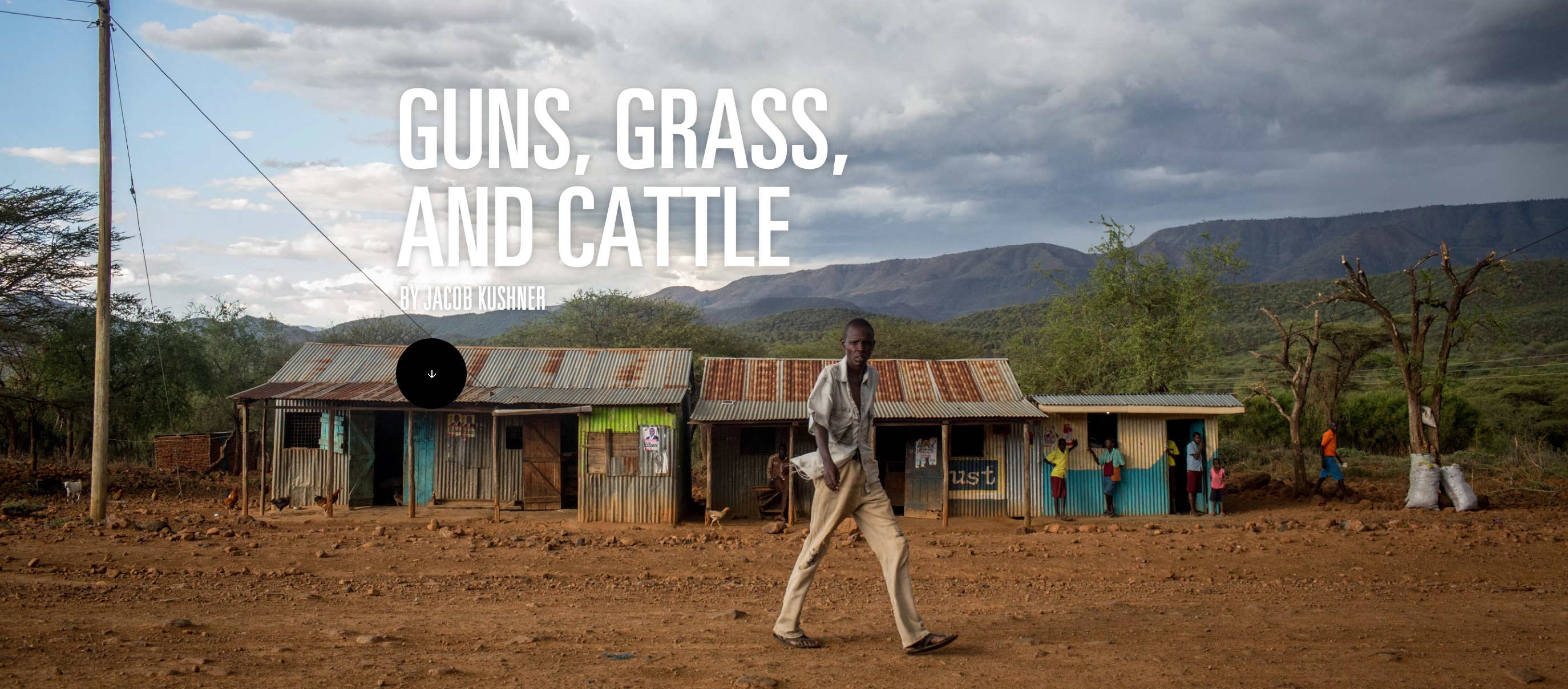

Witnesses say nine days earlier, several truckloads of police officers raided their village, burning their huts and stealing their goats. Officers then threw rocks at the elderly man who had tried to escape. They loaded him onto a truck, dumped him by the side of the road and shot him.

Witnesses say nine days earlier, several truckloads of police officers raided their village, burning their huts and stealing their goats. Officers then threw rocks at the elderly man who had tried to escape. They loaded him onto a truck, dumped him by the side of the road and shot him.