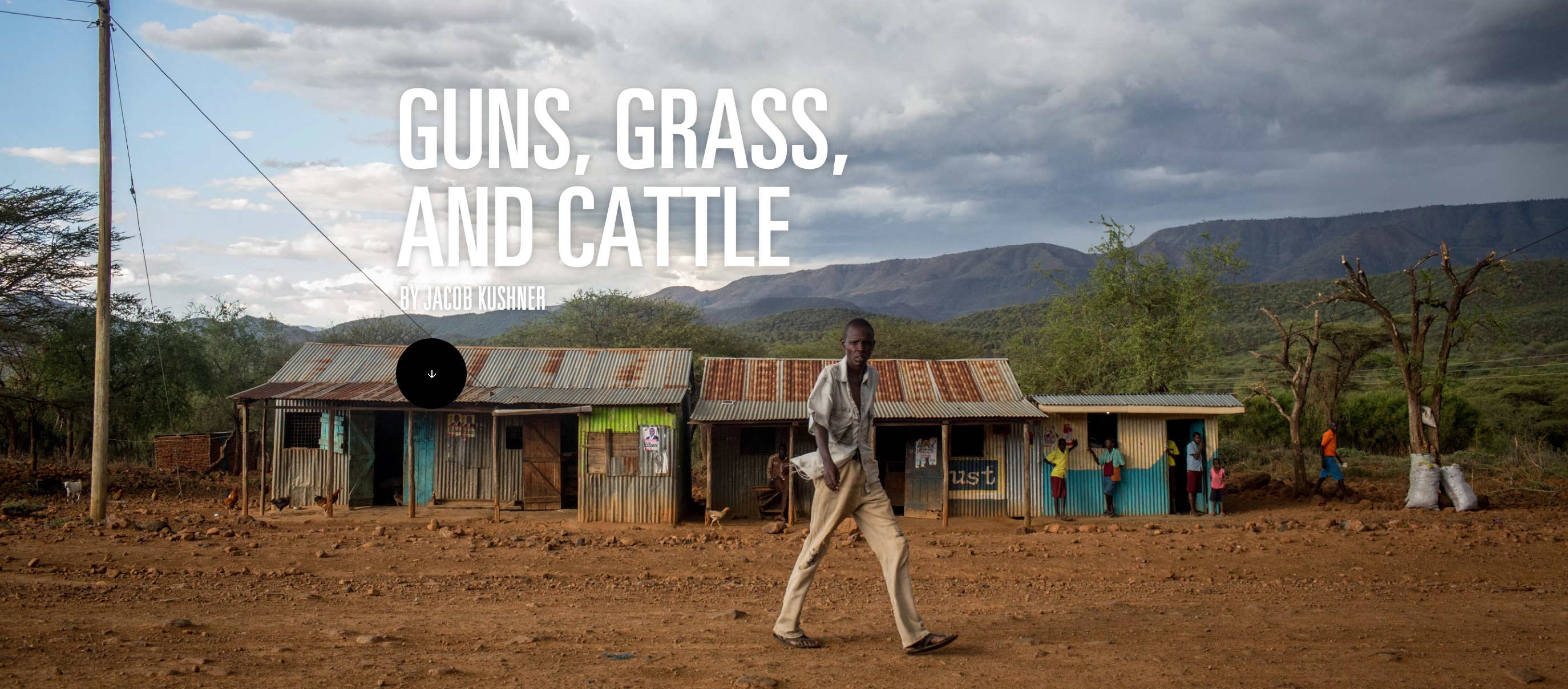

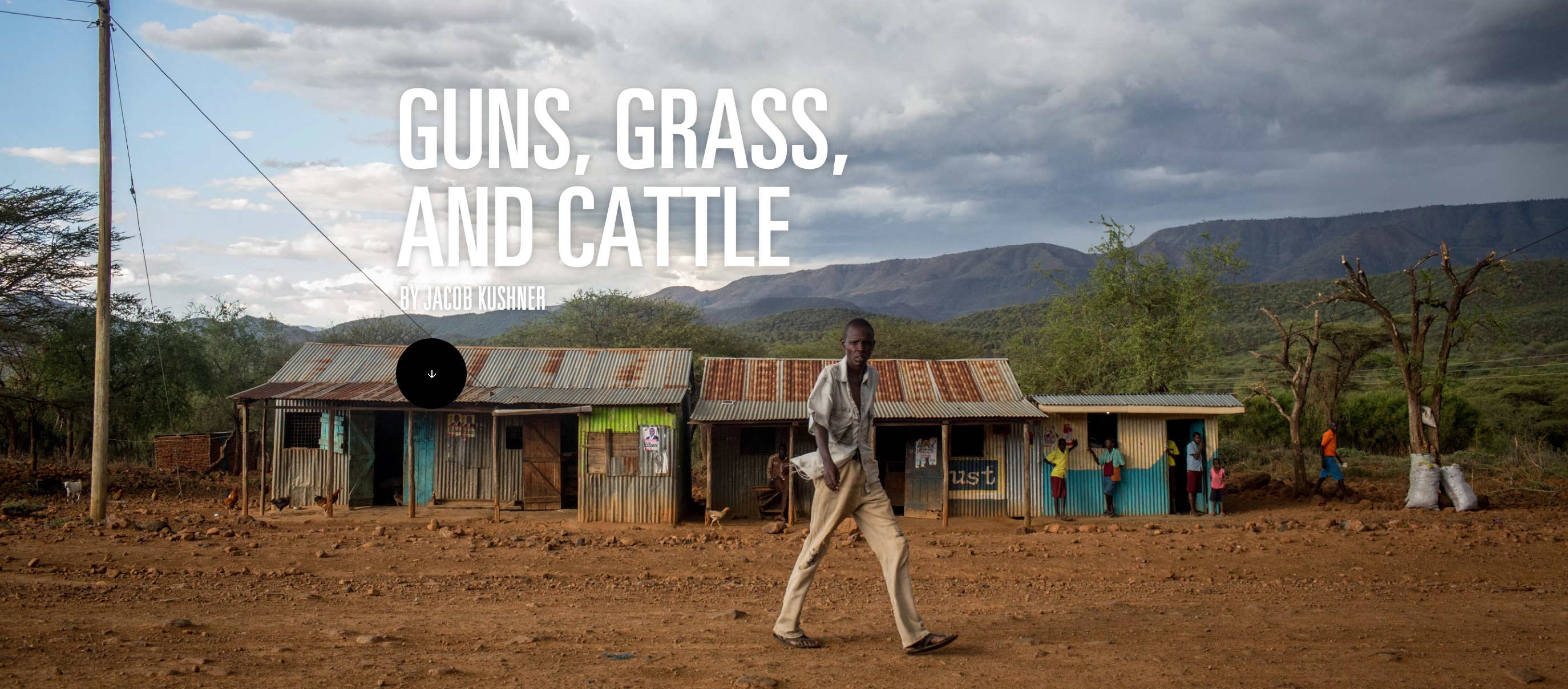

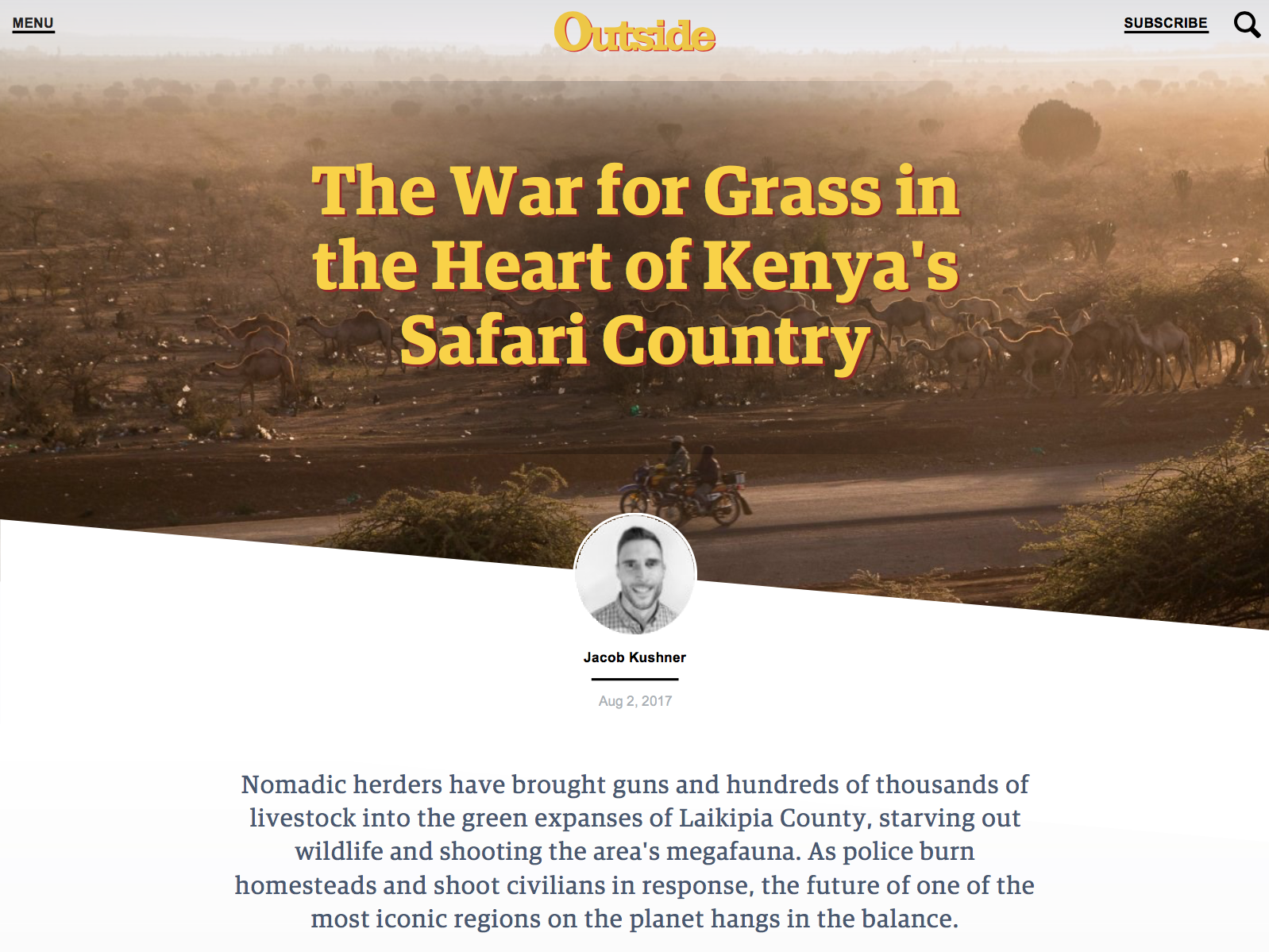

Cornelius said the drive to Arabal would take an hour, but it’s been more like three. Already a full day’s journey from Nairobi, we chanced that by dark we could reach the Arabal river and make it back to the town of Marigat to sleep. But now the sun is inching westward and our car is running out of gas.

This isn’t a place you want to be stranded for the night. Baringo County is in the midst of a war over livestock. A severe drought has forced Pokot herders to drive their cows and goats from the dry flatlands up into the beautiful mountains above Lake Baringo in search of grass. But this land is inhabited by Tugen, and the Tugen are struggling to feed their own livestock as it is.

In central Kenya, grass and vegetation can be a matter of life and death, and not just for the animals. Pastoralists depend upon milk and meat for their livelihoods. Deprived of that income, entire communities can become food insecure. For many families, livestock are their only assets: they have no bank accounts, no land to farm.

Combine those stakes with the fact that experts believe there are 530,000 to 680,000 guns in circulation among civilians in Kenya. Guns have long been traded across Kenya’s porous border with Somalia, but some have recently been traced to Uganda and South Sudan. Most herders who carry them do so for self-defense—to protect their animals from raiders. But others use them to raid.

Some of the Pokot who have crossed into the administrative region of Arabal this year fall into the latter category. Since the drought began late last year, there have been dozens of shootouts between Tugen, Pokot, and the police. Thousands of heads of livestock have been stolen, though just how many thousands is anyone’s guess.

Some of the Pokot who have crossed into the administrative region of Arabal this year fall into the latter category. Since the drought began late last year, there have been dozens of shootouts between Tugen, Pokot, and the police. Thousands of heads of livestock have been stolen, though just how many thousands is anyone’s guess.

Survivors of these shootouts speak of the Pokot as if they were immune to bullets, as if they were sharpshooters who never missed, as if their ammunition were infinite. But survivors are hard to find.

Read the feature story at Roads & Kingdoms. Reported with Anthony Langat, photos by Will Swanson.

Witnesses say nine days earlier, several truckloads of police officers raided their village, burning their huts and stealing their goats. Officers then threw rocks at the elderly man who had tried to escape. They loaded him onto a truck, dumped him by the side of the road and shot him.

Witnesses say nine days earlier, several truckloads of police officers raided their village, burning their huts and stealing their goats. Officers then threw rocks at the elderly man who had tried to escape. They loaded him onto a truck, dumped him by the side of the road and shot him.

Last year at primary schools in western Kenya, social scientists were busy performing dirty skits in front of hundreds of children. The script went like this:

Last year at primary schools in western Kenya, social scientists were busy performing dirty skits in front of hundreds of children. The script went like this:

Young people across the continent aspire to careers in Africa’s blossoming information and communications technology (ICT) sector. But many encounter major barriers that prevent them from finding jobs in the industry. “We have a lot of young people. But unfortunately they come from neighborhoods that don’t have a lot of opportunities,” says Tim Nderi, the chief executive officer of Mawingu Networks.

Young people across the continent aspire to careers in Africa’s blossoming information and communications technology (ICT) sector. But many encounter major barriers that prevent them from finding jobs in the industry. “We have a lot of young people. But unfortunately they come from neighborhoods that don’t have a lot of opportunities,” says Tim Nderi, the chief executive officer of Mawingu Networks.