Donors claimed they would fix Fabienne Jean’s body. They broke her heart instead.

In Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the lakes are flooding farmland, swallowing communities and leading to deforestation, baffling climate scientists.

Jacob Kushner

Story and photos by Jacob Kushner for National Geographic

Uncertainty over land ownership is playing out across Haiti as the country attempts to attract foreign investment in tourism, mining, manufacturing, and agriculture—often without clear knowledge of who, precisely, owns what.

Read: The New Yorker

Allison Shelley

In the aftermath of disaster, Haitians ask what makes a city

Port-au-Prince was decimated when a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck Haiti in January 2010. Within weeks, settlements began to appear on a barren landscape, shacks and tents spreading over dusty plains. They called it Canaan, the biblical promised land where Moses led the Israelites out of slavery–the land of milk and honey. “This Canaan has the same history,” one pastor, who was among the first to move there, told me. “This is our honey.”

But in Canaan, as in any city, people—the rich and the poor, the powerful and weak, the complacent and the desperate—were destined to get in one another’s way.

Read: VQR (Spring 2017)

As featured in Longreads

Immunologist Fatiha El Hilali started trying to counter fake news about vaccines after seeing a close friend die from Covid-19 (Credit: Kang-Chun Cheng)

“If I can be provocative, shouldn’t we be doing this study in Africa, where there are no masks, no treatments, no resuscitation?” said Jean-Paul Mira, head of intensive care at Cochin hospital in Paris. “A bit like as it is done elsewhere for some studies on Aids. In prostitutes, we try things because we know that they are highly exposed and that they do not protect themselves.”

Read: BBC Future

With support from the Pulitzer Center

In northern Kenya, researchers are working to prevent a dangerous coronavirus – MERS – from jumping from camels to humans. But climate change is complicating their task.

Part of our BBC Future series, Stopping The Next One, with Harriet Constable and The Pulitzer Center.

READ: BBC

The discovery of a novel mosquito on Guantanamo Bay reveals how globalization is threatening to unleash the next pandemic. Part of our BBC Future series, Stopping The Next One, with Harriet Constable and The Pulitzer Center.

READ: BBC

Read the full story at Guernica

Support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and Haiti Grassroots Watch.

Haiti’s earthquake shattered several cities, but it also birthed another. A place with space for the dead is a place with space for the living. And in post-earthquake Haiti, space was in short supply. Called Canaan, after the biblical holy land, a place defined by death has come alive.

Read: Pacific Standard

Photography for BBC, The Coronavirus 10 Times Deadlier than Covid-19. Part of the Pulitzer Center-supported series, Stopping The Next One.

Farmer Remy Augustin, 54, prepares the ground to plant maize on a plot owned by his niece near Caracol, Haiti, December 10, 2019. Handout by Allison Shelley

A decade after an earthquake killed more than 200,000 people, farmers in Haiti are waiting to receive compensation for their land used to build an industrial park. Located in Haiti’s northern region, the $300 million Caracol Industrial Park opened in 2012 and now employs approximately 15,000 people, most of whom work in clothing factories there.

In 2018, farmers who had been evicted from their land in 2011 struck a rare deal with the IDB to provide Caracol’s 100 most vulnerable families with new, titled land.

Read the full story at the Thompson Reuters Foundation (PLACE). Reporting supported by The Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting.

Can cities function without a government? In Canaan, Haiti, residents give it a try.

Nine years ago, Canaan 1 was little more than a nameless, hilly swath of land patchworked by boulders and cinder blocks marking where people hoped to one day see proper houses, a hospital, a school, a police station and a basketball court.

Today, the neighborhood is one of many rapidly expanding areas of Canaan, Haiti’s newest city – named for the biblical promised land – home to between 280,000 and 320,000 people.

“We wanted to show the state who we are – that we can put down more than just one or two dollars here,” says Evenson Louis.

Read: U.S. News & World Report

Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Without titles, residents risk losing any investment they make and cannot use their property as collateral

CANAAN, Haiti – On a street of rocks and white dust in the centre of one of the world’s newest cities, Alisma Robert pointed to an array of electric cabling strung between rickety wooden poles.

“It wasn’t EDH that built that pole,” said Robert, referring to Haiti’s national electricity provider.

“It was us.”

Nearly everything in the city of Canaan, which was founded in 2010 after a catastrophic earthquake, was built by residents without government help.

After waiting two years for electricity, Robert and his neighbours collected money from each household, erected the wooden poles, and wired up the cables to the house of a family who were connected to the grid.

“I’m a citizen – but not for the moment. I don’t have the benefits of a citizen. We don’t have drinkable water … No public toilets. The government doesn’t do anything for the people who live here.”

Read the full story at Reuters PLACE. Funding for this story was provided by the Pulitzer Center.

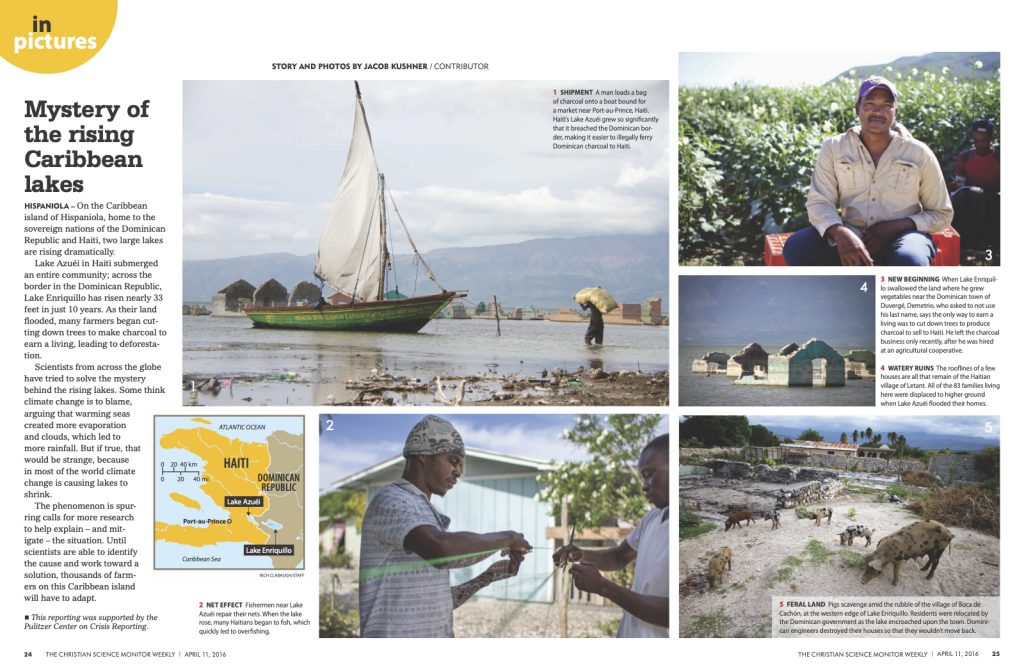

HISPANIOLA – On the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, home to the sovereign nations of the Dominican Republic and Haiti, two large lakes are rising dramatically.

Lake Azuéi in Haiti submerged an entire community; across the border in the Dominican Republic, Lake Enriquillo has risen nearly 33 feet in just 10 years. As their land flooded, many farmers began cut-ting down trees to make charcoal to earn a living, leading to deforestation.

Scientists from across the globe have tried to solve the mystery behind the rising lakes. Some think climate change is to blame, arguing that warming sea created more evaporation and clouds, which led to more rainfall. But if true, that would be strange, because in most of the world climate change is causing lakes to shrink.

The phenomenon is spur- ring calls for more research to help explain – and mitigate – the situation. Until scientists are able to identify the cause and work toward a solution, thousands of farmers on this Caribbean island will have to adapt.

The phenomenon is spur- ring calls for more research to help explain – and mitigate – the situation. Until scientists are able to identify the cause and work toward a solution, thousands of farmers on this Caribbean island will have to adapt.

This reporting was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Juliana Pierre at her home in the Dominican Republic. The denial of her attempt to get the national identity card to which she was legally entitled led to the mass exodus and deportation of Dominican citizens of Haitian descent. (Photo: Jacob Kushner)

The Dominican Republic built its economy on the backs of Haitian immigrants and their descendants. Now it wants them gone.

FOND BAYARD, Haiti—On April 28, 2009, Julia Antoine gave birth to a girl in a hospital in the town of Los Mina, in the Dominican Republic. Her husband, Fritz Charles, couldn’t be there—he was busy working his job at a chicken farm.

In the coming days, the couple named the girl Kimberly. When the family went home, Antoine was given a document from the hospital noting the birth, the date, and the word hembra, or female. They didn’t bother trying to get Kimberly an official birth certificate. Although Antoine and Charles had spent many years living and working in the Dominican Republic, they were Haitian citizens, and it was well known that Dominican officials routinely denied birth certificates to children born to Haitian parents if, like Antoine and Charles, the parents couldn’t furnish passports or other legal documents.

Still, Kimberly was, by law, entitled to Dominican citizenship. Yet in 2015, she was deported along with her mother.

Kimberly and her mother now live in a lean-to hut made of sticks in a refugee camp on borrowed land in Haiti. Their predicament offers a glimpse into what happens when a nation that bestowed citizenship on people born within its territory decides to take that citizenship away.

Read the full longform feature at TakePart. Reporting for this article was funded by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and through a Daniel Pearl Investigative Journalism Initiative Fellowship from Moment Magazine.