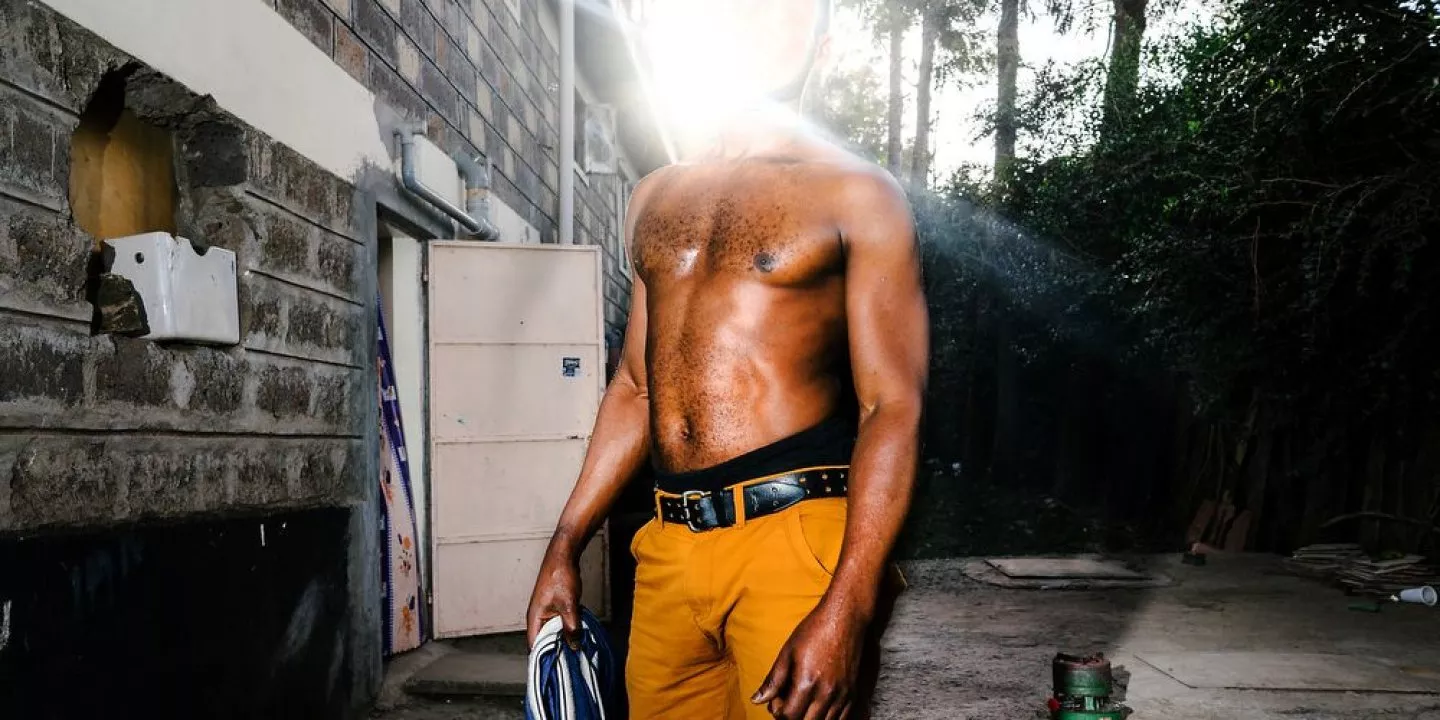

Fenced in: Some refugees at Kakuma are segregated for special protection. /Jake Naughton

At Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya, workers face few humane options

From Turkey to Pakistan, from Iran to Ethiopia, refugee workers are being forced to make painful choices regarding the future of more than 21 million refugees, part of a record 65 million displaced persons around the world. They must choose between political and economic refugees, individuals and families, the healthy and the sick, the elderly and unaccompanied children, gay and straight. They try to move those most in need of help to the front of the line for resettlement somewhere safe.

But when it comes to triaging the world’s humanitarian crises, there are few humane choices.

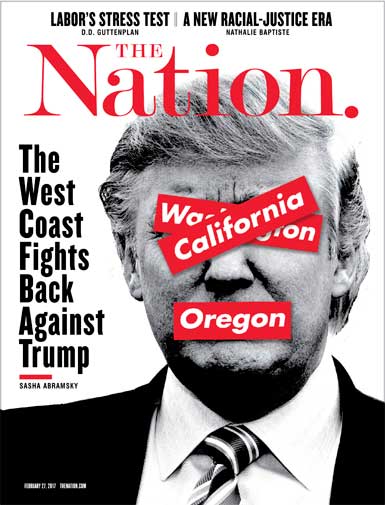

Read in the February 27, 2017 edition of The Nation Magazine.

nerate solid evidence of progress to show funders.

nerate solid evidence of progress to show funders.

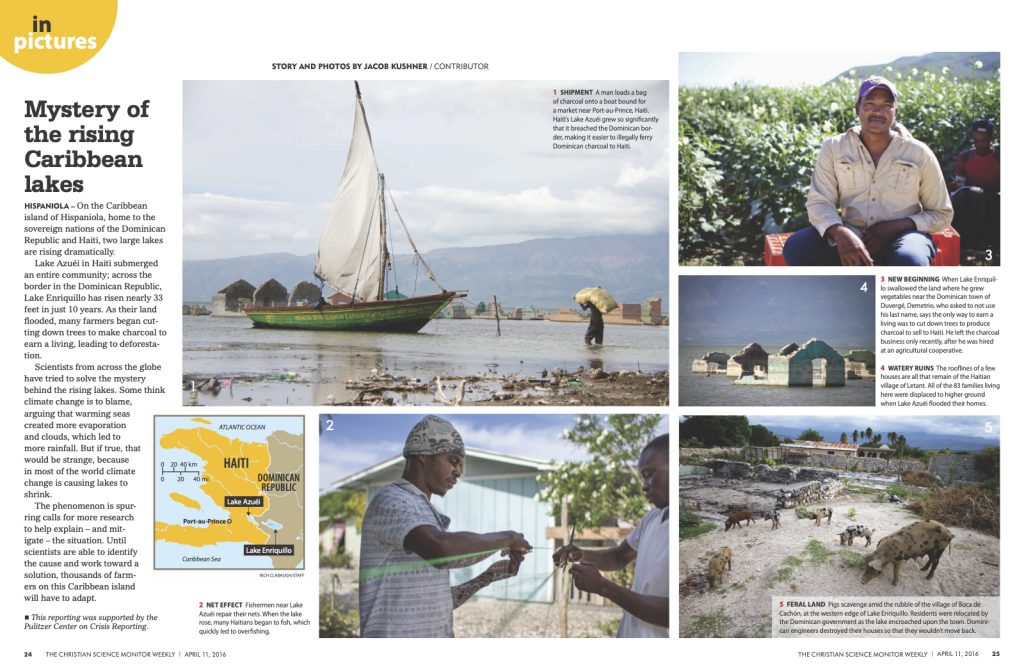

The phenomenon is spur- ring calls for more research to help explain – and mitigate – the situation. Until scientists are able to identify the cause and work toward a solution, thousands of farmers on this Caribbean island will have to adapt.

The phenomenon is spur- ring calls for more research to help explain – and mitigate – the situation. Until scientists are able to identify the cause and work toward a solution, thousands of farmers on this Caribbean island will have to adapt. When Europeans began arriving in the New World at the end of the 15th century, they used the region to source silver, gold, coffee, and wool. Today, China is the foremost trading partner with several Latin American countries, and buys oil from Venezuela, Mexico, and Ecuador; iron ore from Brazil; beef from Argentina; and copper from Chile and Peru.

When Europeans began arriving in the New World at the end of the 15th century, they used the region to source silver, gold, coffee, and wool. Today, China is the foremost trading partner with several Latin American countries, and buys oil from Venezuela, Mexico, and Ecuador; iron ore from Brazil; beef from Argentina; and copper from Chile and Peru.