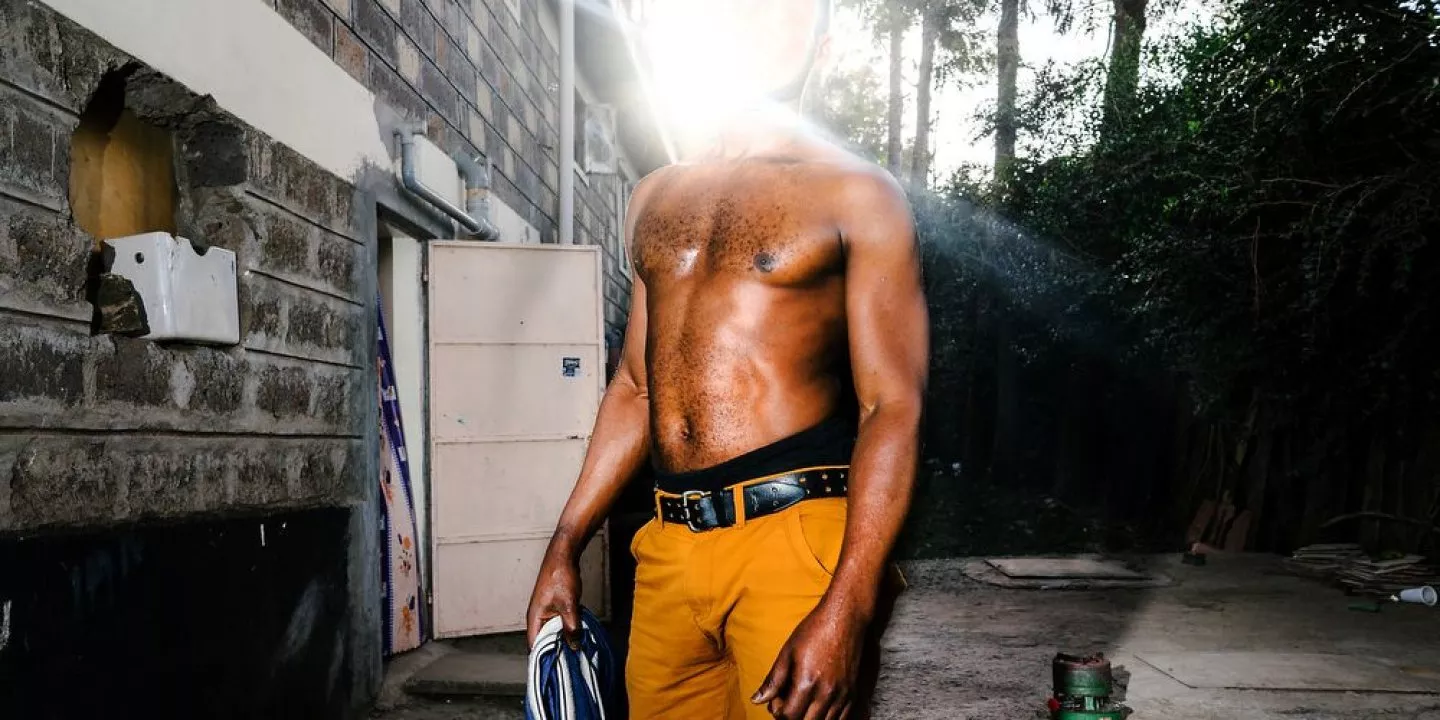

Elias Kimaiyo says the Kenya Forest Service has burned down his home repeatedly as part of a push to evict him and other members of the Senger, an indigenous tribe, from the forests where they have lived for generations. “Most of the time,” Kimaiyo says, “I just live in fear.” / TONY KARUMBA

Another chapter in the World Bank’s fraught relationship with indigenous peoples who live on or near land targeted for development.

By Jacob Kushner, Anthony Langat, Michael Hudson and Sasha Chavkin

It was a morning routine: Elias Kimaiyo woke up, went outside his family’s mud-and-thatch home and climbed a hill. His goal: see where Kenya Forest Service officers were heading that day as they trudged into the forest from a nearby ranger station. Like thousands of his fellow tribespeople, he spent many of his days worrying about whether his family would be the next to be evicted by gun-toting rangers.

One morning in late 2011, Kimaiyo saw that KFS officers were heading in another direction. He went home and worked with his wife, Janet, harvesting their small corn crop in a clearing in the forest. In the afternoon, he decided to check again.

This time, when he climbed the hill, he could see a group of rangers heading toward his house. Kimaiyo ran home. He and his wife began grabbing their things—blankets, utensils, a mattress—and hiding them in the brush. They could see their neighbors’ homes burning. Kimaiyo’s one-year-old son sat in the dirt, crying, as his mom and dad carried armfuls of their belongings deeper into the forest.

Kimaiyo and his wife fled with their son to the other side of a river. They hoped the KFS officers would somehow miss their house in the dense forest.

They didn’t.

Kimaiyo watched, he says, as flames consumed his house and what was left inside—tables, chairs, the bed frame, even the mattress, which the rangers had discovered poorly hidden in the brush and tossed onto the fire.

It was the fourth time, Kimaiyo claims, that Kenya’s government had destroyed his home since the 2007 launch of a forest conservation project that the World Bank said would “improve the livelihoods of communities participating in the co-management of water and forests.”

Read the full ICIJ investigation at The Huffington Post or at PRI’s The World.

This is the latest installment of “Evicted and Abandoned,” an examination of the hidden toll of development financed by the World Bank. The project is a collaboration between the ICIJ and The Huffington Post, with contributions from journalists around the globe.

Witnesses say nine days earlier, several truckloads of police officers raided their village, burning their huts and stealing their goats. Officers then threw rocks at the elderly man who had tried to escape. They loaded him onto a truck, dumped him by the side of the road and shot him.

Witnesses say nine days earlier, several truckloads of police officers raided their village, burning their huts and stealing their goats. Officers then threw rocks at the elderly man who had tried to escape. They loaded him onto a truck, dumped him by the side of the road and shot him.