Story and Photography by Jacob Kushner for the Florida Center for Investigative Reporting and Type Investigations.

foreign policy

The Voluntourist’s Dilemma

New York Times Magazine

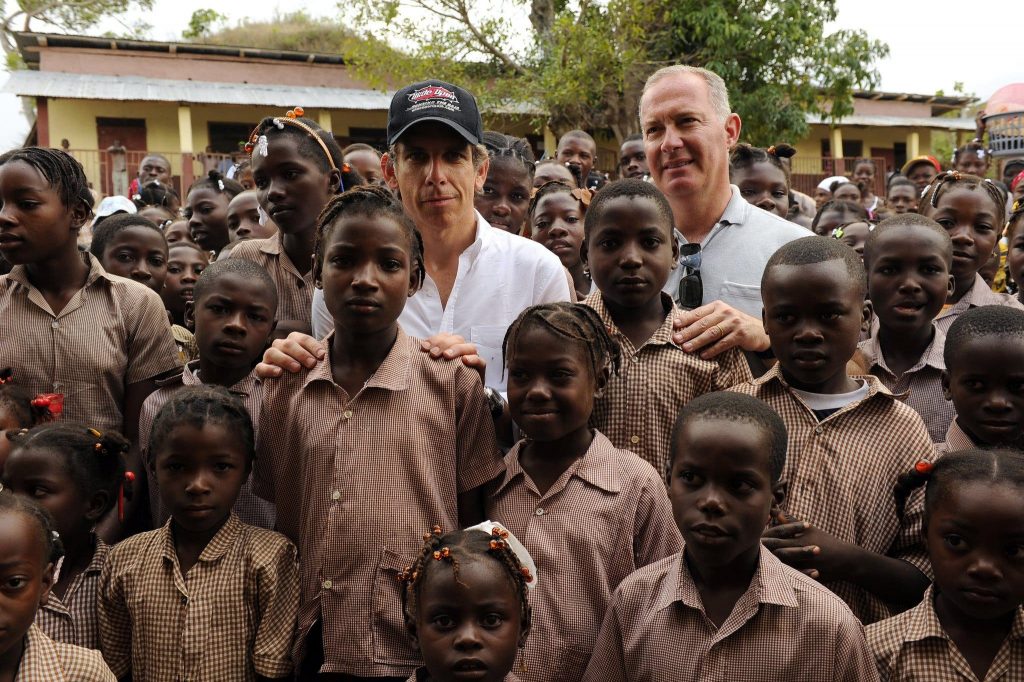

Photo: Ben Stiller visiting Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in April 2010 as part of a school-rebuilding project in which he was involved. Kevork Djansezian/Getty Images

Each year, 1.6 million voluntourists descend upon the Haitis of the world.

Read: The New York Times Magazine

A U.S. State Department Travel Warning for Visitors to the United States [Satire]

Vocativ

Vigilantes go on patrol in September near the U.S.-Mexico border outside Brownsville, Texas.

Reuters/Rick Wilking

“Visitors belonging to a minority race should use particular caution when traveling to areas of the United States where police officers may be present.”

“LGBTQ travelers should instead consider going to Uganda, where only one targeted murder of an LGBT individual occurred in 2011, compared with 30 that year in the United States.”

“Muslims traveling to America should be aware that federal operatives routinely attempt to entrap Muslims into terrorist plots.”

“Violent and sometimes fatal attacks, including armed carjackings, drive-by shootings, burglaries, and kidnappings can occur at any time and in any location, particularly in cities. Travelers to big cities should therefore avoid crowds.”

Read the full satire – originally published by Vocativ.

The British Empire’s Homophobia Lives On

The AtlanticThe first anti-gay laws on the African continent have become the target African LGBTQ-rights activists, who argue that homophobia, not homosexuality, was an import from the West.

Read: The Atlantic

Kenya Could be the Next Country to Strike Down a Colonial-Era Law Against Homosexuality

WNYC The Takeaway

Jake Naughton

The law in question is a colonial-era ban on “carnal knowledge against the order of nature” is part of the penal code in dozens of former British colonies. Many of them are former British colonies with the exact same law on the books.

The activists who brought the case contend that the law is used to exploit and extort, and that it is used to justify discrimination against LGBT people. Opponents have said they will consider alternative measures if the law is overturned, including, potentially a referendum.

Joining The Takeaway to explain what’s at stake is Jacob Kushner, a freelance journalist based in East Africa. Listen to the full interview at WNYC’s The Takeaway. Produced by Beenish Ahmed.

Haiti and the failed promise of US aid

The Guardian

Jacob Kushner

A decade after Haiti’s 2010 earthquake, nothing symbolises America’s failure to help the nation “build back better” than a new port that was promised, but never built.

After sinking tens of millions of U.S. taxpayer dollars into an ill-advised plan to build a new seaport, the US quietly abandoned the project last year. It is the latest in a long line of supposed solutions to Haiti’s woes that have done little – or worse – to serve the country’s interests.

Read: The Guardian’s The Long Read

Supported by the Pulitzer Center.

America Is Still Fighting a War on Marijuana—In Congo.

Columbia Global Reports

North Kivu, DR Congo | A woman going through a terraced tea field. Farmers in places like Congo who see cannabis as a profitable, stable crop must grow it at their peril. | Photo MONUSCO / Abel Kavanagh

Some of eastern Congo’s small-scale farmers are benefiting from a surprising—and illegal—crop.

Cannabis has become a major source of income for tens of thousands of farmers in Congo’s unstable east. It isn’t hard to see the appeal. “Cannabis (is) a robust plant which is easy to grow, requires little labor outside of harvesting and drying, yields several harvests per year, and can be harvested as early as six months from sowing,” writes Ann Laudati, a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who has interviewed more than 100 cannabis farmers in eastern Congo. “They’re making a living off it,” said Laudati. “They’re not getting rich, but they’re surviving.”

Congo isn’t alone. “The highest levels of cannabis production in the world take place on the African continent,” according to the UN. In 2005, Africa produced an estimated one-fourth of all global cannabis. In 2005, seventeen African countries reported that cannabis use was on the rise, including Congo. Be it by land or by sea, the drug also makes its way outside Congo’s porous borders. Quite possibly it’s what’s being smoked by western expats and humanitarians in African cities as far away as Nairobi.

But there’s one major factor limiting the crop’s proliferation: Cannabis is illegal in Congo, as it is in almost every African country. Since 2011, there have been more cannabis seizures in Africa than anywhere else in the world. Africa’s crackdown on cannabis reflects an international narrative that blames cannabis for all manner of the continent’s ills–the product of a century of European and U.S. pressure meant to stop it. According to the RAND Corporation, “in no Western country is a user at much risk of being criminally penalized for using marijuana. “ At a time when the United States is rapidly decriminalizing marijuana at home, it continues to endorse a narrative that demonizes the drug abroad.

Read the full article at Columbia Global Reports.

Uganda Attempts to Shut Down Controversial Silicon Valley-Funded Schools

Columbia Global Reports

School children in Malindi, Kenya, February 2018. Photo by Ian Ingalula, Creative Commons.

Bridge International Academies was conceived in 2007 to be the McDonald’s of global education, promising to better educate poor students using Nooks and standardized curriculums for as little as $6 to $7 a month. Using tablets and standardized curriculums in each country, Bridge operates more than 520 schools, teaching some 100,000 students in Uganda, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria and India. It’s currently expanding in Asia with dreams of reaching an ambitious 10 million students across the world by 2025.

But Some African parents may be uneasy about the idea of a western-conceived company disrupting something they hold so dear: control over their children’s education. Bridge threatens to globalize—or perhaps, to westernize—the sector on which many Africans bank their families’ futures.

Read the full story at Columbia Global Reports.

Congo’s Cannabis

OZY.com

Christopher Furlong/Getty

In a nation known for minerals, a controversial crop is on the rise.

Before he started growing weed, Koti spent his days digging holes and tunnels, mining for morsels of gold. He would smoke weed — or bangias he calls it — to overcome his fear of the darkness that he faced underground. As a teen, he saw a tunnel collapse, trapping five fellow miners — only one was rescued. “It’s dangerous,” says Koti, of the illegal minerals trade that many eastern Congolese families depend on. “People were dying.”

The tragedy frightened him, but with no other source of income, he was back at the mine the next day. Then, in 2007, a foreign mining company kicked Koti and the other small-time miners off the land. With no other job, he bought cannabis seeds from a neighbor, planted them and, six months later, harvested a crop of cannabis that measured in the kilos. “I had no other job,” says Koti, who asked that his real name be withheld out of fear of authorities. “So I decided to start growing marijuana.”

The Democratic Republic of Congo, Africa’s second-largest nation by area, is known for nefarious trade in copper, coltan, cobalt, tin and other minerals. But now, tens of thousands of Congolese like Koti are setting their sights on a different sort of illegal resource: cannabis. The United Nations estimates that Africa produces 10,500 metric tons of cannabis — a fourth of all the marijuana in the world. Between 27 million and 53 million Africans use the drug, making up about one-fourth of all weed users worldwide.

But while cannabis farming comes without the physical fears that accompany mining, it carries its own share of risks, wrapped in politics from across the Atlantic. Decades of U.S. and international pressure are a key reason why cannabis cultivation is illegal in Congo. In 1961, the U.S. voted in favor of the U.N. Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which added marijuana to the list of drugs that were banned internationally. The way to solve America’s drug “problem” was by pinching off the global supply, or so the thinking went.

Farmers can’t receive international aid to grow an illegal crop. It also leaves them vulnerable to harassment from corrupt police officials.

The penalization of cannabis in Congo is endorsed by the U.S. at a time when many states are decriminalizing the drug at home. In Afghanistan, the U.S. has funded “alternative livelihood” programs to shift Afghan farmers away from cannabis. And in 2005, the U.S. vetoed an international attempt to “reschedule” cannabis as a less dangerous substance — a move that could have opened the doors to deregulation.

The penalization of cannabis in Congo is endorsed by the U.S. at a time when many states are decriminalizing the drug at home. In Afghanistan, the U.S. has funded “alternative livelihood” programs to shift Afghan farmers away from cannabis. And in 2005, the U.S. vetoed an international attempt to “reschedule” cannabis as a less dangerous substance — a move that could have opened the doors to deregulation.

Read the full feature at OZY.

Rejected asylum: From Karachi to Germany and back again

Al Jazeera

Jacob Kushner for Al Jazeera

A lawyer and his family fled death threats in Pakistan and came to Germany only to face terrorism. Now, they’re being forced to go home.

Salzhemmendorf, Germany – Late one summer night in this quiet village, a Molotov cocktail came flying through the window of the apartment where a Zimbabwean refugee and her three young children lived.

In the apartment next door, an asylum seeker from Pakistan who calls himself Mr Khan heard nothing. He was sitting at his computer with his headphones on, watching videos on the internet with news from Karachi. He and his family had fled Pakistan for Europe in 2012 after some of his colleagues – lawyers who were Shia Muslim – had been murdered by Sunni Islamic extremists.

When he heard a loud banging on his apartment door, he opened it to find a police officer, who ushered him and his family outside. The building smelled of smoke, and Khan surveyed the wreckage: The Molotov cocktail had destroyed the bedroom it was thrown into. It was the room in which the woman’s 11-year-old son usually slept on a mattress on the floor. By chance, he was sleeping in his mother’s room that night, which may have saved his life.

Outside, “I heard the sound of the fire brigade,” Khan said. “If they did not come, this whole building could have been finished.”

After Khan’s building was attacked by xenophobic Germans, he wondered whether Germany would accept their asylum applications, and allow them to stay.

“Tomorrow, I don’t know what will happen,” Khan said. “Maybe Germany will say, ‘Out!'”

In fact, it did.

Read the full story at Al Jazeera. This is the 6th article in a 7-part series.

On Haiti and the Ethics of Disaster

Center for Journalism Ethics

/ JACOB KUSHNER

The death toll from Hurricane Matthew in Haiti—now officially at 336, though likely far higher—is a big part of why the world is paying attention to Haiti right now. It’s in the headlines, it’s in the ledes. It’s the reason news agencies continuously hunt for the highest figures: The higher your death toll, the more fresh, the more ominous your reporting appears, and the more likely it is that TV news stations, newspapers and news websites will choose your story over your competitor’s.

We should care that hundreds of people have died. But we shouldn’t only care when a storm hits. More than 9,000 Haitians have died from cholera in the six years since the United Nations introduced the disease there. Diarrhoeal diseases kill at least 4,600 Haitians each year. Those diseases are usually brought on by lack of clean water and sanitation — things with relatively simple and low-cost fixes that neither Haiti’s government nor the international aid community has invested in sufficiently to fix.

A friend of mine who works for a major aid organization in Haiti messaged me last week that “it’s awful trying to get to the south with the bridge down, blocked roads, etc. So sad.” She’s talking about a bridge on the same road I traveled back in 2010 to cover hurricane Thomas as it struck Haiti’s south. Indeed, bridges in Haiti fall frequently when storms hit. Without them, aid workers can’t get to the affected areas easily, or at all.

How many of us have opened our wallets in the past five years to donate to the construction of bridges in Haiti — or roads?

More to the point, how many news outlets that are gaining clicks and ad revenue by reporting on the current death toll in Haiti bothered to report on any solutions to Haiti’s chronic infrastructure or health problems in the past? Absent any solutions-oriented coverage, the recent barrage of news about the tragic toll of Hurricane Matthew feels an awful lot like disaster porn.

Read the full Op/Ed at the UW-Madison Center for Journalism Ethics or at MediaShift.

Is Latin America’s China Boom Even Bigger than Africa’s?

Columbia Global Reports When Europeans began arriving in the New World at the end of the 15th century, they used the region to source silver, gold, coffee, and wool. Today, China is the foremost trading partner with several Latin American countries, and buys oil from Venezuela, Mexico, and Ecuador; iron ore from Brazil; beef from Argentina; and copper from Chile and Peru.

When Europeans began arriving in the New World at the end of the 15th century, they used the region to source silver, gold, coffee, and wool. Today, China is the foremost trading partner with several Latin American countries, and buys oil from Venezuela, Mexico, and Ecuador; iron ore from Brazil; beef from Argentina; and copper from Chile and Peru.

According to a new book, The China Triangle: Latin America’s China Boom and the Fate of the Washington Consensus, by Boston University global development professor Kevin P. Gallagher, Chinese investment in Latin America is outpacing even its famed liaison with Africa.

Gallagher argues that the Washington Consensus—by which the U.S. pressured Latin American countries to open their markets to free trade and deregulation during the 1990s—failed to help those states develop. “While the United States wasn’t paying attention, Latin America quickly became of the utmost strategic importance for China—as a source for many of the key natural resources it needs to grow its economy and the appetites of more than a billion people,” he writes.

But therein lies the hitch in Gallagher’s thesis. The antiquated notion that the U.S. and China are in a sort of dichotomous or binary economic arms race—a sense highlighted by the “triangle” reference upon which his book is titled—overlooks the fact that these two nations cannot possibly account for all of Latin America’s gains and losses during the two decades that he studies. If Gallagher’s strongest argument is that China’s Latin American presence is surprisingly large, his weakest is that it is almost singularly responsible for the region’s recent growth.

Read the full book review at Columbia University Global Reports.

Deported From Their Own Country

TakePart

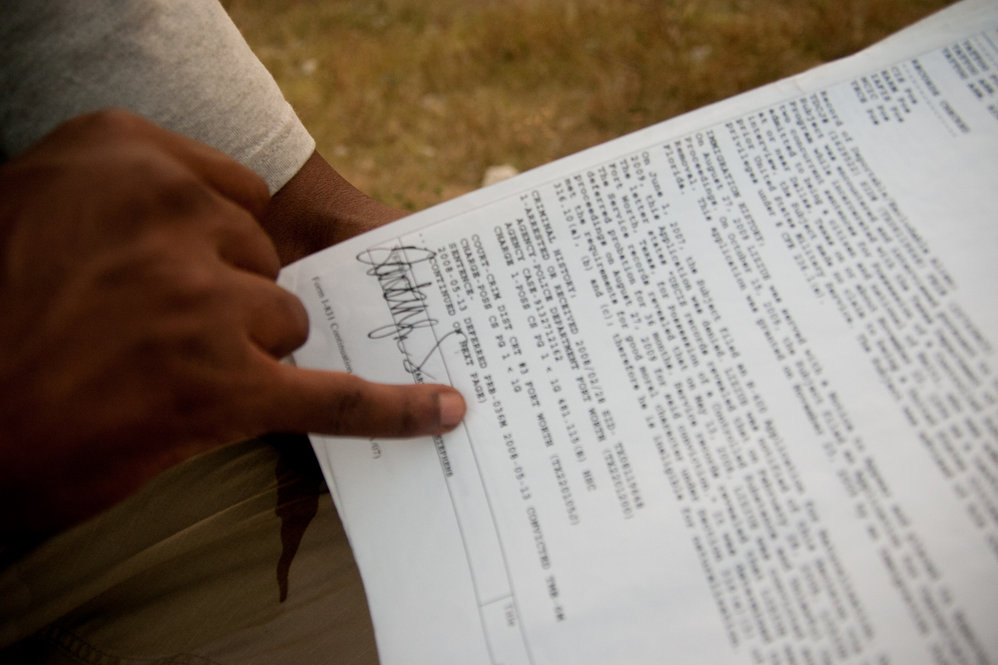

Juliana Pierre at her home in the Dominican Republic. The denial of her attempt to get the national identity card to which she was legally entitled led to the mass exodus and deportation of Dominican citizens of Haitian descent. (Photo: Jacob Kushner)

The Dominican Republic built its economy on the backs of Haitian immigrants and their descendants. Now it wants them gone.

FOND BAYARD, Haiti—On April 28, 2009, Julia Antoine gave birth to a girl in a hospital in the town of Los Mina, in the Dominican Republic. Her husband, Fritz Charles, couldn’t be there—he was busy working his job at a chicken farm.

In the coming days, the couple named the girl Kimberly. When the family went home, Antoine was given a document from the hospital noting the birth, the date, and the word hembra, or female. They didn’t bother trying to get Kimberly an official birth certificate. Although Antoine and Charles had spent many years living and working in the Dominican Republic, they were Haitian citizens, and it was well known that Dominican officials routinely denied birth certificates to children born to Haitian parents if, like Antoine and Charles, the parents couldn’t furnish passports or other legal documents.

Still, Kimberly was, by law, entitled to Dominican citizenship. Yet in 2015, she was deported along with her mother.

Kimberly and her mother now live in a lean-to hut made of sticks in a refugee camp on borrowed land in Haiti. Their predicament offers a glimpse into what happens when a nation that bestowed citizenship on people born within its territory decides to take that citizenship away.

Read the full longform feature at TakePart. Reporting for this article was funded by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting and through a Daniel Pearl Investigative Journalism Initiative Fellowship from Moment Magazine.

Did Obama Avoid the Difficult Questions in Kenya?

OZY.com

Till Muellenmeister/Getty

In an age of terrorism, many countries — the United States among them — face a difficult balance between security and civil rights. For Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, the fight against al-Shabab is no less than “existential.” But human rights groups here say the way Kenya is fighting terrorists will only cause instability and insecurity in the long run. When Muslims see their peers extorted, or worse, by the police, the natural response is anger. A few may even be drawn into the arms of the terrorists, says Mgandi Kalinga, an investigator with local human rights group Haki Africa. A few is all it takes. And so, “the security situation in Kenya is compromised by the government itself,” Kalinga said.

More than any other U.S. president in history, Barack Obama has the chance to shape the course of Kenya’s fight against al-Shabab, not just because of his Kenyan ancestry, but because the United States has helped fund it and train those who are carrying it out. His visit to Kenya over the weekend offered an unprecedented opportunity to influence its parameters.

Did Obama dodge the difficult questions?

Read the full story at OZY.

Obama Heads to a Kenya in Turmoil on His First Visit to the Country as President

VICE Magazine

VICE News.

Millions of Kenyans are celebrating the long-awaited return of Barack Obama, who on Friday will visit his father’s homeland for the first time as president to attend the 2015 Global Entrepreneurship Summit in Nairobi.

Obama’s visit will focus on economic development and counterterrorism efforts within the country against the Somali Islamist group al Shabaab, but it comes amid widespread abuse by Kenyan security forces of Muslims, refugees, and journalists. This has raised worries among rights advocates that he risks lending undue legitimacy to one of Africa’s more unscrupulous regimes.

Obama is visiting a country whose human rights record has taken a notably downward turn. Following years of steady attacks from al Shabaab militants within Kenya, including an assault on Nairobi’s Westgate shopping mall in 2013 that killed 67 and the massacre of 147 people at a university in Garissa earlier this year, local security forces are said to consistently engage in extrajudicial activity in the name of fighting terrorism, and are accused of harassing journalists and undermining press freedoms.

Read: VICE